Peer Reviewed

Slide Injury Leading to Bacteremia and Sepsis in a Pediatric Patient

Case Report Insights: For an in-depth look at the Photoclinic case report below and an interview with the authors, visit www.consultant360.com/videos/case-bacteremia-and-sepsis-pediatric-patient.

An 8-year-old girl presented to an outside community emergency department (ED) with 2 weeks of joint pain impeding her ability to walk and progressive abdominal pain.

History. The patient had a history of well-controlled asthma and eczema. According to her mother, the patient scraped her right arm on a slide at a local fair approximately 2 weeks prior to presentation. Later that day, the patient began having right knee pain and weakness, which progressed to pain in the right arm, neck, hip, thigh, knee, and calf in the days after her injury. She also reported pain in the left knee, thigh, and lower leg. The patient’s pain progressed to inability to bear weight on bilateral lower extremities approximately 1 week after the initial onset of her symptoms, and the right knee and right elbow had become progressively more swollen in the days following the injury.

The patient had gone to her local ED several times since the onset of her extremity pain. She also had progressive abdominal pain and decreased appetite but no fever. The mother said that the patient had group A streptococcus pharyngitis diagnosed seven times in the past 6 months; the first three infections were not treated, and her most recent infection was diagnosed 4 days before the current presentation and treated with an injection of intramuscular penicillin.

Diagnostic testing. Laboratory workup was completed during this visit to the ED (Table 1). C-reactive protein and procalcitonin were not obtained. A urinalysis was also obtained (Table 2).

Table 1. Significant laboratory values of the patient. | ||

Analyte | Value | Reference Range |

White Blood Cell (WBC) | 22.9 x 10-3 uL | 7.0-13.0 x 10-3 uL |

Hemoglobin | 10.1 g/dL | 11.6-13.0 g/dL |

Sodium | 130 mmol/L | 138-145 mmol/L |

Aspartate Transferase (AST) | 60 IU/L | 10-140 IU/L |

Albumin | 1.6 g/dL | 3.4-5.0 g/dL |

Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) | >140 mm/hr | 0-10 mm/hr |

Table 2. Significant urinalysis values of the patient. | ||

Analyte | Value | Reference Range |

White Blood Cell (WBC) | 23 /HPF | 0-5 /HPF |

Red Blood Cell (RBC) | 7 /HPF | 0-3 /HPF |

Bacteria | NEGATIVE | NEGATIVE |

Mucous | RARE /HPF | RARE /HPF |

Epithelial Casts | RARE /HPF | RARE /HPF |

Plain radiographs showed soft tissue swelling with joint effusion of the right elbow and no acute findings of the right knee. Her vital signs were within normal range for her age except for hypertension (135/70 mm Hg).

She was then transferred to our children’s hospital, where a physical examination revealed a swollen, warm, and tender right knee and right elbow, as well as muscular pain to palpation of the right thigh, right calf, right neck, left hip, and left inner thigh. Petechial rash was seen on the bilateral lower extremities. Several hours after transfer, the patient developed a fever of 102.7°F with associated tachycardia, meeting the criteria for systematic inflammatory response syndrome.

She was given a dose of ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg. A respiratory viral panel was positive for coronavirus HKU1 (not COVID-19). We consulted with rheumatology specialists, who determined that the patient met the criteria for rheumatic fever according to the Jones criteria. The patient was started on naproxen 325 mg twice per day, with oxycodone 0.1 mg/kg every 4 hours as needed. An echocardiogram was ordered. The orthopedics team was also consulted, who recommended magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the entire body with contrast, including brain, chest, abdomen, pelvis, bilateral upper extremities, and bilateral lower extremities.

As the patient was awaiting scheduling of the MRI on the second day of hospitalization, her blood culture from admission returned positive for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), suggesting bacteremia. The antibiotic regimen was immediately changed from ceftriaxone to vancomycin 15 mg/kg every 6 hours. The echocardiogram revealed a mobile echogenic mass (presumed vegetation) adhered to the mitral valve chordal attachment, as well as probable vegetation on the ventricular surface of the aortic noncoronary cusp.

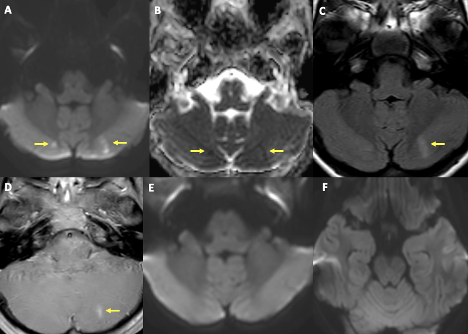

With the new results, the patient was presumed to have endocarditis and septic arthritis. After consulting with the cardiologist on call, the patient was transferred to the cardiac intensive care unit. The entire body MRI demonstrated multiple locations of fluid collections involving both upper extremities and both lower extremities. There were intramuscular fluid collections around the left shoulder, left hip, right distal thigh, and right lower leg, as well as joint effusions of the right elbow, left hip, and both knees (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Contrast enhanced MRI revealed presence of variably sized intramuscular abscesses around the left scapula (yellow arrows in A), left acetabulum (yellow arrow in B), and tibia (yellow arrow in C). Large subperiosteal abscess is present adjacent to the tibia (long red arrow in D) and small intraosseous abscess is seen within the tibia (short red arrow in D). Note ill-defined areas of diffuse soft-tissue enhancement around the right shoulder, left hip, and knee joints (blue star in A, B, and D) represents cellulitis. Multiple nodular lesions demonstrated in lung fields compatible with septic emboli (white arrow in E).

The patient developed septic shock upon returning from the MRI and was too unstable to travel to the operating room for fluid collection drainage. She was intubated and placed on norepinephrine 0.03 mcg/kg/min, dopamine 10 mcg/kg/min, and vasopressin 0.5 milli-units/kg/min. At the bedside, the patient underwent incision, irrigation, and debridement of the right elbow, right distal humerus, right knee, right proximal tibia, right lower-leg intramuscular abscess, as well as aspirations of the left shoulder, left hip, and left knee. She was started on rifampin 10 mg/kg every 12 hours in addition to vancomycin according to the recommendation of the infectious disease specialists. The infectious disease team could not pinpoint how the child acquired MRSA but suggested it may have been from the slide at the local fair or due to another break in the skin. They noted it was especially unusual for a previously healthy child to develop such an aggressive infection.

Once stable, the patient returned to the operating room several times to drain various fluid collections in her joints, muscles, and bones. She was started on heparin 44 units/hr due to the thrombotic-appearing left ventricular mass found on the echocardiogram. She was extubated a few days later and had slow removal of the various drains in her joints. Her antibiotics were switched to ceftaroline 40 mg/kg daily divided every 8 hours and daptomycin 10 mg/kg daily for better penetration into the bones and soft tissue.

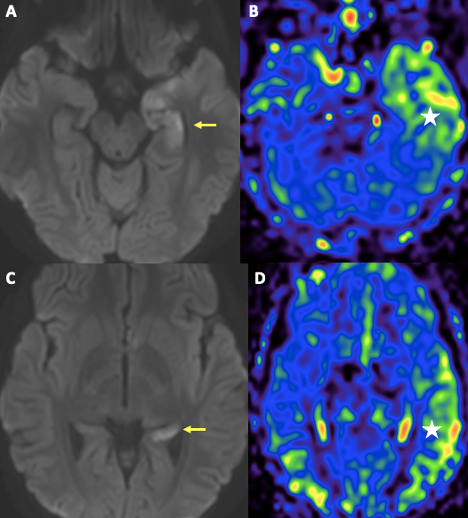

One week into hospitalization, the patient had episodes of auditory and visual hallucinations, followed by staring off to the right side. An electroencephalogram revealed evidence of a lower seizure threshold within the left hemisphere and background slowing (more in the left hemisphere than the right). She was started on levetiracetam 15 mg/kg twice daily and given midazolam 0.05 mg/kg as needed. A computed tomography of the head and brain was within normal limits, but the MRI revealed findings in the supratentorial cerebral parenchyma in the left medial temporal lobe that likely represented postictal changes, in addition to a small acute ischemia/infarction in the right cerebral hemisphere and small subacute ischemia/infarction in the left cerebral hemisphere (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. MRI of the brain showed foci of diffusion restriction in bilateral paramedian cerebellar hemispheres in relatively symmetrical distribution (yellow arrows in A, B). There is fluid-attenuated inversion recovery signal abnormality and contrast enhancement corresponding to lesion in the left cerebellar hemisphere (yellow arrows in C, D). MRI is at the same level from 8 days ago (E, F). The overall imaging pattern is suggestive of acute infarct in the right cerebellar hemisphere and subacute infarct in the left cerebellar hemisphere.

Figure 3. MRI of the brain also revealed presence of diffusion restriction involving nearly the entire left hippocampus, not corresponding to a vascular territory (yellow arrows in A, C). There is corresponding hyperperfusion of the left temporal lobe on non-contrast arterial spin label perfusion imaging (white star in B, D). The findings are likely secondary to a recent ictal event.

The patient was ultimately diagnosed with osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, endocarditis, septic shock, and brain infarction.

Differential diagnoses. The cause of musculoskeletal pain can be difficult to identify in children, especially those who are nonverbal. There are traumatic, neoplastic, rheumatic/inflammatory, and infectious origins to consider. The onset of pain can manifest as limping or an inability to walk, as well as tenderness, visible swelling, or redness around the affected joint or muscle. The patient in this case presented with pain in the right knee that progressed to all extremities.

If the patient’s history demonstrates clear evidence of trauma that could explain the pain, then radiography can determine what type of trauma is affecting the patient. Our patient denied lower extremity trauma. Although a neoplasm is on the differential for musculoskeletal pain, the patient denied B symptoms, such as night sweats and weight loss. The patient’s MRI did not show evidence of tumors or bone marrow infiltration.

The next category on the differential includes rheumatic and inflammatory conditions. Our team initially thought that the patient had acute rheumatic fever (ARF). ARF is an illness caused by a systemic autoimmune reaction to Streptococcus pyogenes pharyngitis.1 The modified Jones criteria is a tool that clinicians may use to diagnose this condition since there is no exact laboratory test for diagnosis.1 For diagnosis of initial ARF, our patient exhibited one major criteria (polyarthritis) and two minor criteria (fever >101.3° F and ESR >60 mm/hr) as well as a documented previous streptococcus infection. Since the patient met the Jones criteria, the hospitalist team as well as the rheumatologist initially believed that she had ARF and started treating her as such, ordering an electrocardiogram, echocardiogram, and starting the patient on naproxen. However, the patient did not improve following naproxen administration, and her blood culture grew MRSA. This points to the diagnosis of ARF being less likely. Although the timeline of the patient’s previous streptococcus infections was unclear, her most recent episode was 4 days before presentation to our hospital, which was much too early to cause ARF; ARF typically develops 2 to 4 weeks after diagnosis of streptococcus infection.1 The initial diagnosis of ARF teaches us the dangers of diagnostic momentum bias and reminds us to continue considering all differential diagnoses before settling on one.

In the same category, juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is another diagnosis to be considered. JIA is a clinical diagnosis that presents as subtle joint pain, especially in younger children. The joint pain may present as morning stiffness, developmental delay, or a recurrent need for the child to be carried. 2 Our patient showed pain in multiple joints but did not meet the criteria for JIA as her pain occurred for only 2 weeks as opposed to 6 weeks for JIA criteria.3 Although reactive arthritis was also on the differential diagnosis (especially considering our patient had a rash on the lower extremities), reactive arthritis usually occurs after an upper respiratory, gastrointestinal, or urinary tract infection, none of which our patient had.4 It is interesting to note, however, that reactive arthritis can have cardiac involvement in 60% to 70% of pediatric cases.4

Growing pains affect whole limbs instead of joints, often bothering an otherwise-well child during the night.2 If the patient’s pain persists and intensifies (as in our patient), growing pains should be excluded as potential causes of joint pain in children. If the patient experiences widespread pain throughout the body as well as fatigue, sleep disturbances, and symmetrical tender points, fibromyalgia should be considered.5 Myalgias can result from trauma but can also be a symptom following a viral infection.

The next category to consider is infectious. Transient synovitis is also another common cause of joint pain in children, usually in the hips. Transient synovitis is postulated to be an inflammatory reaction to a recent infection, typically an upper respiratory infection.6 The pain is not as pronounced as it would be in children with septic arthritis or osteomyelitis and should be considered when these two other conditions have been excluded.6 Despite joint effusions (especially in knees and hips)2 being a commonality between septic arthritis and transient synovitis, the child with transient synovitis appears well and walks with a limp.6 The patient with septic arthritis, however, can experience pseudoparalysis of the limb involved or undergo septic shock.6 A fever also warrants concern for osteomyelitis, septic arthritis, or both. Clinical manifestations of osteomyelitis in children often occur in the leg with redness, swelling, and tenderness in the joint. In addition, a higher body temperature, tachycardia, and a painful limp are more often associated with MRSA osteomyelitis rather than children with methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) osteomyelitis.7 Although not diagnostic for septic arthritis, MRI can identify joint effusions, abscesses, and soft tissue swelling in the patient, which is helpful for later irrigation, debridement, and aspirations of affected areas.6

Treatment and management. The patient was continued on ceftaroline and daptomycin for her MRSA, endocarditis, and acute hematogenous osteomyelitis. As time progressed, the patient was changed from heparin to enoxaparin 1.5 mg/kg every 12 hours for her various thrombi, and she was transferred to the inpatient pediatrics floor. She was discharged on hospital day 25 on daptomycin 11 mg/kg daily via peripherally-inserted central catheter, along with physical therapy, occupational therapy, psychology, infectious disease, cardiology, neurology, orthopedics, and hematology specialist follow-up.

Outcome and follow-up. The patient’s mental status returned to baseline at discharge. Her strength improved and she was able to walk moderate distances with the help of physical therapy. She remained on daptomycin via peripherally-inserted central catheter line for a total of 10 weeks. An echocardiogram performed 3 months after hospitalization revealed resolution of the left ventricular thrombus, and thus enoxaparin was stopped. Levetiracetam was weaned and discontinued by her neurologist, and she continues to be seizure-free. The patient reports occasional stiffness of the left hip joint, which the orthopedist suggests may be related to joint space narrowing and femoral head sclerosis, likely caused by joint damage from the septic arthritis. Otherwise, she can walk long distances unassisted.

Discussion. Bacteremia occurs when an invasive bacterial species enters a person’s bloodstream and can lead to complications when the bacteria travels to various organ systems.8 While literature exists describing bacteremia, endocarditis, septic arthritis, and cerebral infarction in pediatric patients, there is a paucity of case reports detailing all these complications occurring at once. Furthermore, few case reports detail these critical complications in an immunocompetent child.

Infective endocarditis is a condition in which viral, bacterial, or fungal microorganisms cause an acute or subacute endocardial infection.9 Endocarditis may result from septic arthritis or osteomyelitis, and usually presents as persistent fevers or complications of emboli and vegetations on the heart. It affects both children and adults.

Presentations of pediatric endocarditis can vary, as it depends on the extent of cardiac disease in the patient, the involvement of other organs, and the severity of the infective agent,8 which in this case was MRSA. Causative organisms of septic arthritis, in addition to the more common Staphylococcus aureus include Haemophilus influenzae, Salmonella, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, group B streptococci, and gram-negative pathogens.6 The infectious agents that cause osteomyelitis are similar to those listed above, but these conditions typically present as fever and localized pain among children.6

The patient in this case was admitted for persistent fevers and joint pains and was found to have vegetations on her heart. A variety of literature describes endocarditis in a similar manner. In a previous study, musculoskeletal sources accounted for 35% of patients with MSSA septicemia.10 Another case reported a 9-year-old boy with severe hemophilia A who also developed bacterial endocarditis and septic arthritis, despite this being uncommon among patients with hemophilia.11 A subsequent case noted the importance of accounting for invasive group C streptococci because, although rare, the onset of complications like septic arthralgias, bacteremia, endocarditis, and osteomyelitis enhances its prevalence.12

The patient in this study received an echocardiogram and was treated with vancomycin and daptomycin for her endocarditis. Vancomycin was historically recommended initially for treating MRSA infections. However, daptomycin is shown to have better tolerability and bactericidal activity than vancomycin, and even reduced clinical failure in MRSA infections.13 Therefore, our patient was switched to and discharged on daptomycin rather than vancomycin.

This case brings attention to rare adverse effects (such as endocarditis and cerebral infarctions) of a bacterial infection from an injury as trivial as a scrape on a slide. It adds value to the existing literature in its unique presentation of endocarditis with joint pains, which will drive further inquiries about the wide-ranging causes and complications of endocarditis. Our case also highlights the need for a multidisciplinary approach with a variety of hospital subspecialties when treating an invasive bacterial infection such as MRSA.

AFFILIATIONS:

1Harriet L. Wilkes Honors College, Florida Atlantic University, Jupiter, FL

2Nemours Children’s Health, Orlando, FL

CITATION:

Burgess D, Cooper F, Watal P, Ali SA. Slide injury leading to bacteremia and sepsis in a pediatric patient. Consultant. 2023;63(8):e5. doi:10.25270/con.2023.08.000002.

Received January 5, 2023. Accepted April 25, 2023. Published online August 9, 2023.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no relevant financial relationships.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

None.

CORRESPONDENCE:

Felicia Cooper, MD, Department of Graduate Medical Education, Nemours Children’s Health, 6535 Nemours Parkway, Orlando, FL 32827 (Feliciacooper2020@gmail.com)

1. Lahiri S, Sanyahumbi A. Acute rheumatic fever. Pediatr Rev. 2021;42(5):221-232. doi:10.1542/pir.2019-0288

2. Sen ES, Clarke SLN, Ramanan AV. The child with joint pain in primary care. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2014;28(6):888-906. doi.10.1016/j.berh.2015.04.008

3. Kim KH, Kim DS. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: diagnosis and differential diagnosis. Korean J Pediatr. 2010;53(11):931-935. doi:10.3345/kjp.2010.53.11.931

4. Ansell BM. Rheumatic disease mimics in childhood. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12(5):445-447. doi:10.1097/00002281-200009000-00017

5. Foster H, Kimura Y. Ensuring that all paediatricians and rheumatologists recognise significant rheumatic diseases. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23(5):625-642. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2009.07.002

6. Tse SML, Laxer RM. Approach to acute limb pain in childhood. Pediatr Rev. 2006;27(5):170-179. doi:10.1542/pir.27-5-170

7. Peltola H, Pääkkönen M. Acute osteomyelitis in children. New Engl J Med. 2014;370(4):352-360. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1213956

8. Paul JJ, Steele RW. Ankle pain, a swollen neck, and a gallop. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2016;56(7):686-691. doi:10.1177/0009922816677040

9. Guler S, Sokmen A, Mese B, Bozoglan O. Infective endocarditis developing serious multiple complications. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013:bcr2012008097. doi:10.1136/bcr-2012-008097

10. Makki D, Elgamal T, Evans P, Harvey D, Jackson G, Platt S. The orthopaedic manifestation and outcomes of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus septicaemia. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B(11):1545-1551. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.99b11.BJJ-2016-1093.R1

11. Titapiwatanakun R, Pruthi RK, Schmidt K, Slaby JA, Rodriguez V. Bacterial endocarditis and septic arthritis in a patient with severe hemophilia A: a case report. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2009;31(5):344-345. doi:10.1097/mph.0b013e31818c91b8

12. Miles B, Tuomela K, Sanchez J. Severe group C streptococcus infection in a veterinarian. IDCases. 2021;23:e01036. doi:10.1016/j.idcr.2020.e01036

13. Maraolo AE, Giaccone A, Gentile I, Saracino A, Bavaro DF. Daptomycin versus vancomycin for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection with or without endocarditis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10(8):1014. doi:10.3390/antibiotics10081014