Peer Reviewed

Elderly Man With Sudden Vision Loss

A 76-year-old man presents with a sudden severe, painless loss of vision in his left eye. On awakening that day, he became aware of a central black spot in his left field of vision. He noticed a few floaters in the eye but no flashing lights. His right eye does not seem to be affected. He also reports a new onset of generalized head pain and pain on the left side of the jaw after chewing. He has no history of ocular injury or surgery.

The patient has arthritis and diet-controlled hyperlipidemia. He takes methotrexate, hydrocodone, and folic acid.He is allergic to celecoxib and experiences GI upset with non-coated aspirin.

The patient's corrected visual acuity is 20/30 in the right eye; in the left eye, he has hand motion vision at 5 ft. There is a 2+ afferent pupillary defect in the left eye. Examination of the visual fields by confrontation shows constriction with a central scotoma in the left eye. Extraocular muscle movements are full with no restrictions, and the intraocular pressures are normal.

Slitlamp evaluation identifies nuclear sclerotic cataracts in both eyes; the anterior segment is otherwise unremarkable. Funduscopic examination reveals a pallid optic disc with a cherry-red spot in the left macula (Figure 1). The blood vessels are more attenuated in the left retina than in the right. Sludging of red blood cells in the retinal vasculature of the left eye is also seen. There is no retinal detachment. No bruits are heard on auscultation of the carotid arteries.

Ocular massage is performed in the office. A regimen of oral prednisone, 60 mg/d, and coated aspirin, 81 mg/d, is initiated. Results of blood tests obtained the same day show an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 84 mm/h; top normal value for this patient is 76/2 = 38 mm/h. The C-reactive protein (CRP) level is 3.2 mg/dL. The complete blood cell (CBC) count is normal. A carotid duplex ultrasonographic scan on the following day reveals bilateral internal carotid plaque with less than 40% stenosis and normal flow velocities. Because of the elevated ESR and CRP values, a temporal artery biopsy is scheduled.

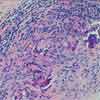

The biopsy findings include acute and chronic inflammation. There is evidence of thickening of the media, destruction of the internal elastic lamina, and panarteritis (Figures 2 and 3). These findings confirm the diagnosis of temporal arteritis.

The patient continues to take oral prednisone. After 2 months, his headache and jaw claudication have resolved; however, the vision in his left eye has not improved. Optic atrophy eventually develops in that eye (Figure 4). The right eye is not affected. The oral prednisone is being slowly tapered. His ESR and CRP values will be monitored, and he is instructed to report any new symptoms.

TEMPORAL ARTERITIS: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Temporal arteritis, also known as giant cell arteritis and cranial arteritis, is a chronic inflammatory disease that may involve blood vessels that supply the optic nerve, retina, and brain.

Temporal arteritis is the most common primary vasculitis that affects white persons, especially those of Scandinavian and Northern European descent.1 The median age of affected patients is 76 years. Temporal arteritis is more common in women than in men, with respective incidences of 72.6% and 27.4%.2-4

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Up to 50% of patients report ocular symptoms.5 Between 70% and 80% of patients present with a pallid (chalky white) swollen disc, known as arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy.5 Less common causes of vision loss in persons with temporal arteritis include nonembolic central retinal artery occlusion, such as was seen in this patient. This occlusion may be the presenting sign in up to 14% of patients; it may also occur simultaneously with the optic neuropathy.3,6

Other ocular presentations include amaurosis fugax (31% of patients); eye pain (8.2%); posterior ischemic optic neuropathy (7.1%); and ocular ischemic syndrome (1.2%). About 10% to 15% of patients present with transient diplopia or frank cranial nerve palsy.2,3,7 It is unclear whether the cause of the ophthalmoplegia is neurogenic (peripheral cranial neuropathy or brain stem ischemia) or myogenic (or- bital or muscle ischemia).8

Nonocular findings include fatigue; anorexia; weight loss; polymyalgia rheumatica; altered mental status; headache; scalp tenderness; scalp necrosis; intermittent jaw or tongue claudication; ear, throat, or neck pain; facial edema; nonproductive cough; dysphasia; angina pectoris; congestive heart failure; myocardial infarction; and stroke.8-12

LABORATORY STUDIES

Laboratory tests for patients with suspected temporal arteritis include measurement of ESR (Westergren method) and CRP level and CBC count. Affected patients often have a mild to moderate normochromic-normocytic anemia with a normal leukocyte and differential count.12 Thrombocytosis is seen in up to 50% of patients.13 A markedly elevated ESR (higher than 40 mm/h) is found in about 90% of patients who have biopsy-proven temporal arteritis.12

The ESR is affected by age and sex. The following formulas are useful for estimating the normal upper values: male = age/2, female = (age + 10)/2.11 Because the ESR also tends to become falsely elevated in the presence of anemia, a CBC count is helpful in patients with suspected temporal arteritis.8

The CRP level is unaffected by anemia and does not tend to vary with age.8,11 When both the ESR and CRP level are elevated, the specificity is 97% for the diagnosis of temporal arteritis in the presence of suggestive clinical findings.2

TEMPORAL ARTERY BIOPSY

This procedure is performed in all patients with suspected temporal arteritis.12 Temporal artery biopsy is 100% specific and up to 95% sensitive for the disease.14 Verification of the diagnosis by biopsy supports the use of systemic corticosteroid therapy, which often is required for up to a year and may be associated with severe systemic complications.12

Temporal artery biopsy is typically performed unilaterally on the symptomatic side. If the initial biopsy results are negative but clinical suspicion remains high, a biopsy of the contralateral side should be performed.15 There is up to a 5% chance that results of this biopsy will be positive when results of the first biopsy are negative.15,16 A false-negative biopsy may result from discontinuous arterial involvement (intervals of histologically normal-appearing tissue known as "skip lesions"), especially in the setting of an insufficient length of specimen or inadequate sectioning of the histopathologic tissue.7,12

TREATMENT

Initiation of therapy should not be delayed for performance of the temporal artery biopsy, because the artery remains abnormal for at least 2 weeks after corticosteroid therapy is started.12 Whether the initial treatment should consist of high-dose oral prednisone or intravenous methylprednisolone is still debated. If the patient has not yet lost any vision--as in the case of amaurosis fugax--or if the seeing eye is threatened in a patient who has recently lost vision in one eye as a result of temporal arteritis, intravenous methylprednisolone is recommended.12 This treatment is thought to help prevent the onset of blindness in the seeing eye or further loss of vision in the threatened eye.10,11 Without treatment, contralateral eye involvement develops in 50% to 95% of patients, often within weeks.17,18

The systemic corticosteroids can be tapered slowly as the symptoms and laboratory inflammatory markers return to normal.11 Long-term treatment (months to years) may be necessary in some patients.10,11 Alternate-day corticosteroid regimens are not recommended because they have been associated with rebound arteritis.19

PROGNOSIS

Recent research suggests that recovery of vision is unlikely even when intravenous corticosteroids are administered immediately.20 Stabilization of vision during the first week of treatment appears to be the key factor in preventing further vision loss.16

1. Nordborg E, Bengtsson BA. Epidemiology of biopsy-proven giant cell arteritis (GCA). J Intern Med.1990;227:233-236.

2. Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Raman R, ZimmermanB. Giant cell arteritis: validity and reliability of variousdiagnostic criteria. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123:285-296.

3. Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman B. Ocularmanifestations of giant cell arteritis. Am J Ophthalmol.1998;125:509-520.

4. Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman B. Occultgiant cell arteritis: ocular manifestations. Am J Ophthalmol.1998;125:521-526.

5. Hayreh SS, Zimmerman B. Management of giantcell arteritis: our 27-year clinical study: new light onold controversies. Ophthalmologica. 2003;217:239-259.

6. Liu GT, Glazer JS, Schatz NJ, Smith JL. Visualmorbidity in giant cell arteritis: clinical characteristicsand prognosis for vision. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:1779-1785.

7. Goodwin JA. Temporal arteritis: diagnosis andmanagement. In: Focal Points: Clinical Modules forOphthalmologists. Vol. 10, no. 2. San Francisco:American Academy of Ophthalmology; 1992:1-11.

8. Lee AG, Brazis PW. Giant cell arteritis. In: FocalPoints: Clinical Modules for Ophthalmologists. Vol.23, no. 6. San Francisco: American Academy of Ophthalmology;2005:1-13.

9. Skorin L. Neuro-ophthalmic disorders. In: BartlettJD, Jaanus SD, eds. Clinical Ocular Pharmacology.4th ed. Boston: Butterworth Heinemann; 2001:457-459.

10. Kanski J. Neuro-ophthalmology. In: Kanski J,ed. Clinical Ophthalmology. 4th ed. Boston: ButterworthHeinemann; 2000:593-597.

11. Goodwin J. Temporal arteritis, neuro-ophthalmicdisease. In: Onofrey BE, Skorin L, HoldemanNR, eds. Ocular Therapeutics Handbook: AClinical Manual. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: LippincottWilliams & Wilkins; 2005:603-606.

12. Galetta S. Vasculitis. In: Miller NR, NewmanNJ, eds. Walsh & Hoyt’s Clinical Neuro-Ophthalmology.6th ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams& Wilkins; 2005:2333-2426.

13. Foroozan R, Danesh-Meyer H, Savino PJ, et al.Thrombocytosis in patients with biopsy-proven giantcell arteritis. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:1267-1271.

14. Pless M, Rizzo JF 3rd, Lamkin JC, Lessell S.Concordance of bilateral temporal artery biopsy ingiant cell arteritis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2000;20:216-218.

15. Farris B. Temporal artery biopsy. In: FocalPoints: Clinical Modules for Ophthalmologists. Vol.21, no. 7. San Francisco: American Academy ofOphthalmology; 2003:1-10.

16. Niederkohr RD, Levin LA. Management of thepatient with suspected temporal arteritis. Ophthalmology.2005;112:744-756.

17. Beri M, Klugman MR, Kohler JA, Hayreh SS.Anterior ischemic optic neuropathy, VII: incidenceof bilaterality and various influencing factors. Ophthalmology.1987;94:1020-1028.

18. Miller NR, Keltner JL, Gittinger JW. Giant cell(temporal) arteritis. The differential diagnosis. SurvOphthalmol. 1979;23:259-263.

19. Hunder GG, Sheps SG, Allen GL, Joyce JW.Daily and alternate-day corticosteroid regimens intreatment of giant cell arteritis: comparison in aprospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1975;82:613-618.

20. Danesh-Meyer H, Savino PJ, Gamble G. Poorprognosis of visual outcome after visual loss fromgiant-cell arteritis. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:1098-1103.