When Weakness is More Than Deconditioning: ANCA-Associated Small-Vessel Vasculitis

ABSTRACT: Small-vessel vasculitis syndromes associated with the presence of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) can present in older patients with systemic symptoms, including weakness, fatigue, neuropathy, lung disease, and renal failure. The authors review types of ANCA-associated vasculitides, with a focus on eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis and their clinical presentation in older adults. Although thought to be uncommon in older adults, the true prevalence of small-vessel vasculitis is not known in this population. Primary care physicians should be aware of clinical and laboratory features suggestive of this condition as these diseases, if detected early, are often amenable to treatment.

Vasculitis, including the antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)–associated small-vessel vasculitides, can present in older adults. Given the nonspecific symptoms, such as weakness and weight loss, these diseases can easily be overlooked as natural effects of aging or attributed to other conditions in older patients. ANCA-associated vasculitis is believed to be a rare condition, but its true incidence is not known. Some studies have estimated 20 cases per million per year among elderly persons,1,2 but some indicate that the incidence is increasing because of improved diagnostic modalities.3 This article reviews ANCA-associated vasculitides and provides a case study that highlights the importance of swiftly diagnosing the condition in an older adult.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

RELATED CONTENT

Vasculitis Masquerading as an Infection

ANCA-Associated Small-Vessel Vasculitis

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

A Case Study

History. An 89-year-old man presented to the emergency department with a relentless cough, significant bilateral lower extremity edema, and weakness. A computed tomography (CT) scan done 1 year prior for episodic shortness of breath and recurrent pneumonia had revealed possible early interstitial lung disease. Over the year, he had been treated unsuccessfully with inhaled corticosteroids and beta-agonists for new onset asthma, several courses of antibiotics for presumed pneumonia, and furosemide for possible heart failure. Despite this, he remained active by walking more than 25 miles a week, and he married his long-time girlfriend.

Over the 5 to 6 weeks prior to his admission, he began to have weakness that rapidly progressed to the point of being unable to stand without assistance. His weakness was at that time attributed to deconditioning by his primary care physician. Given his continued decline and unclear reason for deconditioning, the patient and his family presented to our institution for a second opinion.

Physical examination. The physical examination was remarkable for asymmetric atrophy of the left quadriceps, diminished but present reflexes, pitting edema in the lower extremities, and scattered, palpable purpuric lesions around both ankles.

Laboratory testing. His aldolase was only minimally elevated and creatinine kinase was normal. The work-up revealed a normocytic anemia with eosinophilia, bilateral lower extremity deep venous thrombosis (VTE), a small pericardial effusion on echo, a markedly elevated C-reactive protein of 42, mildly elevated serum creatinine to 1.3 mg/dL, elevated immunoglobulin E levels, a weakly positive rheumatoid factor with a negative anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide, low titer antinuclear antibody test with a negative extractable nuclear antigen antibody panel, and a negative urinalysis. Chest radiography and CT scan demonstrated bilateral infiltrates and possible pulmonary fibrosis. Notably, infiltrates on chest radiography appeared to be in different locations from prior films.

Testing with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for ANCA was markedly positive for the presence of antibody to myeloperoxidase (MPO).

Treatment. The patient was treated with prednisone for likely small-vessel angiitis with features of eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (EGPA). Within 1 month, his condition greatly improved; his cough resolved, his rash disappeared, and his strength dramatically improved.

Discussion

Vasculitis is categorized by the size of the blood vessels involved: small, medium, or large. In the 1950s, investigators began to recognize diseases associated with arteritis that were not consistent with previously described polyarteritis nodosa (PAN), a medium-vessel vasculitis. Unlike PAN, these diseases all involved small vessels, such as arterioles, venules and capillaries.4 This is an extremely important distinction to understand, and one that is still frequently confused: PAN is clinically and pathologically different from the small-vessel vasculitides, involves medium-sized arteries, and it would be later discovered is ANCA-negative.5

The ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitides have historically included Wegener’s granulomatosis, microscopic polyangiitis (MPA), Churg-Strauss syndrome, and drug-induced small-vessel vasculitis. However, it is important to note that in 2012, the nomenclature of vasculitides changed.6 Notably, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA) replaced Wegener’s vasculitis; EGPA replaced Churg-Strauss syndrome; and immunoglobulin A vasculitis replaced Henoch-Schönlein purpura.

With regard to EGPA, which was seen in our case patient, the age of onset greatly varies, but the mean age of onset has been reported to be 40 to 50 years.7 One case report from Japan noted a significant number (47%) of patients who were over the age of 60 and several patients who were in their 80s.8 It is not clear exactly how common ANCA-associated vasculitides and EGPA are in the older population, as many of the symptoms of these diseases can be easily misattributed to old age, comorbidities, or even cancer.

However, clinicians should be mindful of ANCA-associated vasculitides in a differential diagnosis, as the disease might be associated with, and even precede the detection of, an underlying malignancy. There are several case reports in the literature of ANCA-associated vasculitis and EGPA presenting as paraneoplastic processes due to underlying lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and other malignancies.9-11

In addition, there is an increased risk of venous thromboembolic events, such as deep VTE and pulmonary embolism in patients with underlying ANCA-related vasculitis and EGPA. In a recent study that included more than 200 patients with EGPA, 8% of patients were found to have VTE and the risk factors identified in those patients with clotting included older age, male sex, and prior stroke. ANCA status and renal involvement did not seem to predict the development of VTE in these patients.12

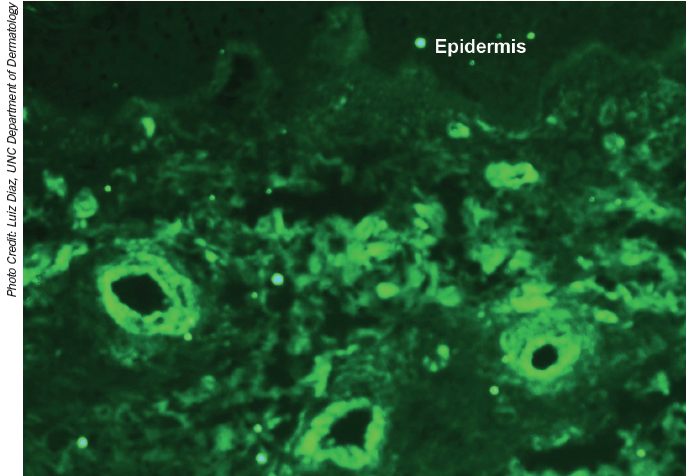

Typical histology from a skin biopsy of leukocytoclastic vasculitis.

Diagnosing ANCA-Associated Vasculitides

ANCAs are a group of autoantibodies against antigens in the cytoplasm of neutrophil granule proteins and monocytes. The antibodies induce distinct patterns on immunofluorescent imaging (ie, the cytoplasmic ANCA [C-ANCA] and the perinuclear ANCA [P-ANCA]).7 Current testing utilizes ELISA with purified and specific antigens to detect antibodies directed against proteinase 3 (PR3) and MPO antigens. Most C-ANCA staining patterns are associated with antibodies to PR3, and most P-ANCA staining patterns are associated with antibodies to MPO proteins. This type of ELISA testing to detect antibodies to MPO or PR3 is highly specific in its association with small-vessel vasculitis. Although specific, it is important to remember that ANCA testing may still be negative in patients with GPA (10% of cases), MPA (20%-30%), and EGPA (30%-50%).4

Small-vessel angiitis and capillary inflammation lead to the classic features of these diseases, including purpura, pulmonary hemorrhage, mononeuritis multiplex due to nerve ischemia, and glomerulonephritis. Infarction of muscle, including cardiac muscle, can occur, leading to weakness and myocarditis. Each of these diseases is clinically distinguished by the presence or absence of pulmonary disease, asthma, upper airway inflammation, and renal disease (Table 1).

Classically, patients are described as moving through 3 phases of the disease over the course of several years—beginning with allergic rhinitis and asthma, progressing to eosinophilic organ infiltration, and finally presenting with the findings of a small-vessel vasculitis. In reality, patients may present at any point along this spectrum.13

• GPA. GPA typically presents as a pulmonary-renal syndrome with glomerulonephritis and pulmonary hemorrhage, associated upper airway disease, such as rhinitis, sinusitis and nasal septal necrosis, and pathological evidence of granulomatous inflammation. The majority (80%) of patients with GPA will at some time have renal involvement, and 90% will have antibodies to PR3-ANCA.14

• MPA. Clinically, MPA is similar to GPA but it does not include the presence of granulomas. MPA is the most common cause of pulmonary-renal syndrome in adults and many of these patients have glomerulonephritis.4

• Drug-induced. Drug-induced ANCA-associated vasculitis is important to keep in the differential diagnosis and may be associated with many medications, most notably propylthiuracil in patients with underlying hyperthyroidism. Patients with drug-induced ANCA vasculitis may present with predominantly cutaneous manifestations and almost all have a high titer MPO-ANCA.15

Direct immunofluorescene showing staining of dermal blood vessels with complement component 3.

EGPA in Older Patients

EGPA is clinically differentiated from the other ANCA-associated vasculitides by its association with asthma and eosinophilia. Originally described by Churg and Strauss in 1951,16 it is also known as allergic angiitis and granulomatosis. Patients may present with reactive airways, asthma type symptoms, and pulmonary infiltrates years prior to the other features of the vasculitis.7,17 It may be associated with glomerulonephritis, but is less likely than GPA and MPA to do so—with only 25% of patients having renal involvement. It is the least common of the described ANCA-associated vasculitides, and may be more likely to have associated neuropathy, gastrointestinal involvement, and cardiac involvement.18

Clinical features that should indicate EGPA include refractory asthma, pulmonary infiltrates, eosinophilia and rhino-sinusitis in a patient with evidence of small-vessel angiitis, including systemic symptoms, purpura, neuropathy, high inflammatory markers, or glomerular disease. Although some cases of EGPA have been attributed to the use of leukotriene receptor antagonists, there is no clear evidence that this is a causal relationship. A more recent study found no clear pathogenic role of these agents in the development or progression of the disease.19

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

RELATED CONTENT

Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis

Vasculitis Associated With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Although classified as one of the ANCA-associated vasculitides, only 40% to 70% of patients with EGPA are ANCA-positive (Table 2). Most ANCA-positive EGPA patients have antibodies directed against the MPO-ANCA antigen. In one series of patients, patients who were ANCA-positive were more likely to have overt evidence of small-vessel vasculitis with progressive renal disease and pulmonary hemorrhage. Those who were ANCA-negative were more likely to have predominantly asthma-type symptoms.18,20

More recent data support the observation that patients with EGPA are a heterogeneous group and that ANCA-positivity may be predictive of outcomes and prognosis. In a recent series of patients, ANCA-positive patients were less likely to have cardiac involvement and less likely to die (5% vs 12%) over a 5-year period, but were also more likely to have relapses of their vasculitis (35% vs 22%) when compared with ANCA-negative patients.21

In 1990, the American College of Rheumatology set criteria to help with the diagnosis of what had been known at the time as Churg-Strauss syndrome. Under this criteria, EGPA must have at least 4 of the following 6 features: asthma, eosinophilia, mononeuropathy or polyneuropathy, migratory or transient pulmonary infiltrates, paranasal sinus abnormalities, and biopsy with evidence of extravascular eosinophils. It is important to keep in mind that this schema is meant as a guide to differentiate EGPA from other vasculitides. Without asthma and eosinophilia, the patient likely has MPA or GPA (depending on the clinical features and the presence or absence of granulomas). Without evidence for vasculitis, the patient likely has an asthma-related diagnosis.7

Pulmonary involvement can vary and may present as asthma, migratory pulmonary infiltrates on radiography, or even chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. One study noted 20% of patients to have pleural effusions.18 There are also reports of interstitial lung disease and pulmonary fibrosis in association with ANCA-associated vasculitis and EGPA.22,23

Treatment

Given the rarity of EGPA, there is a lack of strong data on treatment options and overall prognosis. Most studies report an overall better prognosis in patients with EGPA compared with the other ANCA-associated vasculitides and a good response rate to corticosteroids. There have been small studies examining the use of cyclophosphamide and other immunosuppressive agents, but most patients still require long-term steroids for control of their asthma and respiratory symptoms.18 Patients who have multiple unexplained symptoms and evidence of systemic disease with the presence of auto antibodies may significantly benefit from being referred as early as possible to a rheumatologist or specialist. ■

Debra L. Bynum, MD, is a clinical associate professor at University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC.

C. Adrian Austin, MD, is a fellow in the division of geriatric medicine at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC.

Anna Conterato, MD, is a second-year resident in internal medicine at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC.

References:

1.Ghosh S, Bhattacharya M, Dhar S. Churg-strauss syndrome. Indian J Dermatol. 2011;56(6):718-721.

2.Watts RA, Lane SE, Bentham G, Scott DG. Epidemiology of systemic vasculitis: a ten-year study in the United Kingdom. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(2):414-419.

3.Mansi IA, Opran A, Rosner F. ANCA-associated small-vessel vasculitis. Am Fam Physician. 2002;65(8):1615-1620.

4.Jennette JC, Falk RJ. Small-vessel vasculitis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(21):1512-1523.

5.Pagnoux C, Seror R, Henegar C, et al. Clinical features and outcomes in 348 patients with polyarteritis nodosa: a systematic retrospective study of patients diagnosed between 1963 and 2005 and entered into the French Vasculitis Study Group Database. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;

62(2):616-626.

6.Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Bacon PA, et al. 2012 revised international chapel hill consensus conference nomenclature of vasculitides. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):1-11.

7.Masi AT, Hunder GG, Lie JT, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Churg-Strauss syndrome (allergic granulomatosis and angiitis). Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33(8):1094-1100.

8.Uchiyama M, Mitsuhashi Y, Yamazaki M, Tsuboi R. Elderly cases of Churg-Strauss syndrome: case report and review of Japanese cases. J Dermatol. 2012;39(1):76-79.

9. Calonje JE, Greaves MW. Cutaneous extravascular necrotizing granuloma (Churg-Strauss) as a paraneoplastic manifestation of non-Hodgkin's B-cell lymphoma. J R Soc Med. 1993;86(9):549-550.

10. Hamidou MA, El Kouri D, Audrain M, Grolleau JY. Systemic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody vasculitis associated with lymphoid neoplasia. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60(3):293-295.

11. Navarro JF, Quereda C, Rivera M, Navarro FJ, Ortuno J. Anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated paraneoplastic vasculitis. Postgrad Med J. 1994;70(823):373-375.

12. Allenbach Y, Seror R, Pagnoux C, et al. High frequency of venous thromboembolic events in Churg-Strauss syndrome, Wegener's granulomatosis and microscopic polyangiitis but not polyarteritis nodosa: a systematic retrospective study on 1130 patients. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(4):564-567.

13. Dunogue B, Pagnoux C, Guillevin L. Churg-Strauss syndrome: clinical symptoms, complementary investigations, prognosis and outcome, and treatment. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;32(3):298-309.

14. Duna GF GC, Hoffman GS. Wegener's granulomatosis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1995;21:949-986.

15. D'Cruz D, Chesser AM, Lightowler C, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-positive crescentic glomerulonephritis associated with anti-thyroid drug treatment. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34(11):1090-1091.

16. Churg J, Strauss L. Allergic granulomatosis, allergic angiitis, and periarteritis nodosa. Am J Pathol. 1951;27(2):277-301.

17. Lhote F, Guillevin L. Polyarteritis nodosa, microscopic polyangiitis, and Churg-Strauss syndrome. Clinical aspects and treatment. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. Nov 1995;21(4):911-947.

18. Sinico RA, Bottero P. Churg-Strauss angiitis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2009;23(3):355-366.

19. Keogh KA, Specks U. Churg-Strauss syndrome: clinical presentation, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, and leukotriene receptor antagonists. Am J Med. 2003;115(4):284-290.

20. Sable-Fourtassou R, Cohen P, Mahr A, et al. Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies and the Churg-Strauss syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(9):632-638.

21.Comarmond C, Pagnoux C, Khellaf M, et al. Eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis (Churg-Strauss): Clinical characteristics and long-term followup of the 383 patients enrolled in the French Vasculitis Study Group cohort. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(1):270-281.

22.Hervier B, Pagnoux C, Agard C, et al. Pulmonary fibrosis associated with ANCA-positive vasculitides. Retrospective study of 12 cases and review of the literature. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(3):404-407.

23.Arulkumaran N, Periselneris N, Gaskin G, et al. Interstitial lung disease and ANCA-associated vasculitis: a retrospective observational cohort study. Rheumatology. 2011;50(11):2035-2043.