Smoking Cessation: How to Make It Work

The health benefits of smoking cessation are impressive—even in those who have smoked for many years (Dr Thomas Petty reports on this topic on page 1385). The risk of lung cancer is reduced by 50% to 70% after 10 years of abstinence, and it continues to decline thereafter.1

Recently, the National Guideline Clearinghouse2 compared smoking cessation recommendations from the Public Health Service,3 the University of Michigan Health System,1 the Singapore Ministry of Health,4 the New Zealand Guidelines Group,5 and the US Preventive Services Task Force.6 Highlights of guidelines from the US groups are presented here.

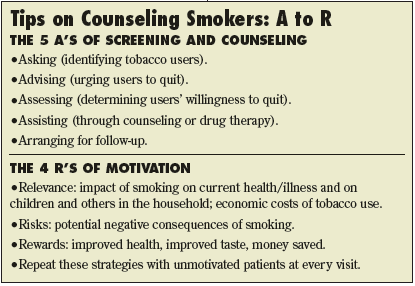

The American groups concur on nearly all aspects of screening and counseling for tobacco use. All the guidelines follow the “5-A” behavioral counseling framework (Box).

SCREENING FOR TOBACCO USE

Ask all patients whether they use tobacco, and document their smoking status at every visit. If the patient is a smoker, ascertain his or her readiness to quit. Studies have shown that advice from a physician to quit smoking increases abstinence rates.1

COUNSELING AND PATIENT EDUCATION

If the patient is ready to stop using tobacco, set a “quit date”; provide personalized advice; offer pharmacologic therapy if appropriate and information on community programs; and arrange follow-up. If the patient is not ready to quit, try to motivate him using the “4 R’s.”

Counseling patients about quitting for as brief a period as 3 minutes is effective in smoking cessation. Intensive intervention (frequently defined as a minimum of 1 weekly meeting for the first 4 to 7 weeks of cessation) and pharmacotherapy are more effective than less intensive interventions and should be used whenever possible. If feasible, try to meet 4 or more times with patients who are attempting to quit. Phone calls and letters may be more cost-effective than follow-up visits at the office.

Cessation strategies. Help the patient create a plan to quit using tobacco:

• Set a quit date and record this on the patient’s chart. Ask the patient to mark the date on a calendar.

• Recommend that the patient inform family, friends, and coworkers of his plan to quit and request their support.

• Have the patient remove cigarettes from home, car, and workplace environments.

• Caution the patient to anticipate challenges (ie, nicotine withdrawal symptoms), particularly during the critical first few weeks.

When to refer. Consider referral to intensive counseling (multisession, group, or individual). Referral considerations include:

• Multiple unsuccessful quit attempts initiated by brief intervention.

• Increased need for skill building (coping strategies/problem solving), social support, and relapse prevention.

• Psychiatric cofactors, such as depression, eating disorder, anxiety disorder, attention deficit disorder, or alcohol abuse.

PHARMACOLOGIC THERAPY

Encourage patients who are attempting to quit to use pharmacologic therapies for smoking cessation. Both nicotine replacement therapy and bupropion significantly improve cessation rates.

Consider the following first-line medications:

• Bupropion SR (sustained release).

• Nicotine gum.

• Nicotine inhaler.

• Nicotine nasal spray.

• Transdermal nicotine (patch).

The following medications are second-line options:

• Clonidine.

• Nortriptyline.

• Combination nicotine replacement therapy.

Combining the nicotine patch with a self-administered form of nicotine replacement therapy (either nicotine gum or nasal spray) is more effective than a single form of nicotine replacement. Encourage patients to use combination therapy if they are unable to quit using a single type of first-line pharmacotherapy.

POTENTIAL HARMS OF SMOKING CESSATION AND PHARMACOTHERAPY

Adverse effects. Weight gain of as much as 30 lb occurs in up to 10% of smokers who quit, and comorbid psychiatric conditions may be exacerbated by cessation of tobacco use.

Pharmacologic agents that are FDA-approved for smoking cessation and their common reported side effects and incidences in patients include2 :

•Bupropion SR: insomnia (35% to 40%) and dry mouth (10%).

•Nicotine inhaler: local irritation in the mouth and throat (40%), coughing (32%), and rhinitis.

•Nicotine nasal spray: nasal/airway irritation and reactions (94%), dependency (15% to 20%).

•Transdermal nicotine: local skin reaction (50%) and insomnia.

•Nicotine chewing gum: mouth soreness, hiccups, dyspepsia, and jaw ache.

•Nicotine inhaler: Cough, mouth and throat irritation.

Pharmacologic agents that are not FDA-approved for smoking cessation and their common reported side effects and incidences in patients include:

•Clonidine: dry mouth (40%), drowsiness (33%), dizziness (16%), sedation (10%), and constipation (10%).

•Nortriptyline: sedation, dry mouth (64% to 78%), blurred vision (16%), urinary retention, light-headedness (49%), and shaky hands (23%).

Precautions in special populations. There is little information on the safety and efficacy of tobacco cessation pharmacotherapy for the pregnant woman, the fetus, or the nursing mother and child. Consider pharmacotherapy for a pregnant patient only when the likelihood of quitting and its potential benefits outweigh the risks of the therapy and continued smoking. Similarly, there is little information on the safety and efficacy of tobacco cessation pharmacotherapy in children or adolescents.

PREVENTION OF RELAPSE

Arrange follow-up either with a phone call or an office visit. Schedule follow-up contact soon after the quit date, preferably during the first week. Extending treatment contacts over a number of weeks appears to increase cessation rates.

Assess patients who have relapsed to determine whether they are willing to make another quit attempt. Congratulate ex–tobacco users who are undergoing relapse prevention on any success, and strongly encourage them to remain abstinent.

For patients who relapse, consider more intensive counseling and reassessment of their pharmacotherapy regimen; encourage them to make another quit attempt. Longterm use of smoking cessation pharmacotherapy may reduce the likelihood of relapse.

REFERENCES:

1. University of Michigan Health System (UMHS). Smoking Cessation. Ann Arbor, Mich: University of Michigan Health System; 2001.

2. National Guideline Clearinghouse. Tobacco Use and Prevention. In: National Guideline Clearinghouse [Web site]. Rockville, Md: National Guideline Clearinghouse: 2001 July 29 (updated 2005 March 14). Available at: http://www.guideline.gov. Accessed May 4, 2005.

3. Public Health Service. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence. Rockville, Md: US Dept of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2000.

4. Singapore Ministry of Health. Smoking Cessation. Singapore: Singapore Ministry of Health; 2002.

5. New Zealand Guidelines Group. Guidelines for Smoking Cessation: Revised 2002. Wellington, New Zealand: National Advisory Committee on Health and Disability; 2002.

6. US Preventive Services Task Force. Counseling to Prevent Tobacco Use and Tobacco-Caused Disease: Recommendation Statement. Rockville, Md: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2003.