Diabetes: 12 Treatment Pitfalls—and How to Avoid Them

ABSTRACT: There is no alternative to being eternally suspicious of underlying problems in the patient with erratically controlled diabetes. Glucose control in those with known diabetes may unravel for a number of reasons, including overeating, inadequate exercise, overinsulinization (typically in patients with marked “glucose bounces”), and inadequate patient education about selection of injection sites and the mechanics of insulin injection. In addition, patients who experience repeated hypoglycemic episodes may overreact to even minor symptoms by overeating carbohydrates at night: the result is an elevation in morning fasting blood glucose levels. Psychological factors, including eating disorders, depression, and anxiety disorders, may upset diabetic metabolic balance. Close physician supervision and patient compliance can lead to better diabetes control.

Key words: type 2 diabetes mellitus, insulin resistance, hyperglycemia

An increasing number of patients with diabetes have difficulty in managing their blood glucose levels. It used to be that patient education, a properly constructed calorie-restricted diet, a patterned exercise program based on lifestyle and ability, and appropriate dosages of oral antidiabetic medication or insulin were usually all that were required to secure optimal control. In more and more patients, however, such control is difficult if not impossible to achieve.

This problem has become clearer with the use of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) as a standard for diabetic control. Measurement of HbA1c and of such cardiac risk factors as lipoprotein(a), homocysteine, and C-reactive protein has led to increasing challenges as the management of diabetes has grown more complex (Box).

New emphasis has been placed on the detection of such diabetic complications as microalbuminuria, which presages nephropathy, as well as subtle forms of retinopathy and neuropathy. These complications may occur extraordinarily early in the course of the disease and must be dealt with as quickly as possible after a definitive diagnosis of diabetes is established.

There is now a greater sense of urgency in controlling hyperglycemia. It is important to be aware of evolving standard and emergency strategies (eg, combination therapy that includes oral agents as well as insulin, new insulin delivery systems, new glucose monitoring technology, and the use of analogs of glucagon-like peptide-1 [GLP-1], dipeptidyl peptidase-4 [DPP-4] inhibitors, and thiazolidinediones [TZDs]).

In a sizable minority of patients—perhaps even a majority—long-term control is difficult, if not impossible, to achieve. Here I describe 12 common treatment pitfalls. I focus on the many possible causes of poorly controlled blood glucose levels, and I outline steps to overcome them.

OVEREATING

1 The most common cause of uncontrolled hyperglycemia is excessive intake of carbohydrates—particularly simple carbohydrates. Patients must remember that most oral antidiabetic agents and subcutaneously injected insulin do not work instantly: if carbohydrates are consumed too soon after the administration of these agents, the blood glucose level may rise rapidly. This is particularly a problem when early morning blood glucose determinations may reflect the “dawn phenomenon,” a possible Somogyi effect, as well as the rapid absorption of breakfast foods, such as fruit, fruit juices, and cereal. Intermediate-acting insulin may not be effective for 4 hours after it is injected. Even regular insulin or even lispro insulin must be administered sufficiently in advance of breakfast to allow the onset of the insulin effect.

Recent research is focusing on the importance of postprandial levels of glucose, which are now considered to be equal in significance to fasting blood glucose levels. Postprandial levels must be controlled adequately with combination therapy.

UNDEREXERCISING

2 It cannot be overemphasized that adequate exercise is necessary for the metabolism of glucose and the avoidance of obesity with subsequent cardiovascular complications. Inadequate exercise and/or activity is a common cause of increased blood glucose levels. The result of underexercising is, therefore, a need for more insulin and/or higher doses of oral antidiabetic agents. Exercise increases the body’s response to both endogenous and exogenous insulin by producing muscle-induced insulin-like hormones. Inadequate physical activity leads directly to increased insulin resistance and hyperglycemia.

Daily walking or use of a stationary bike or treadmill may be good motivators for underexercisers. Planned attendance at a spa or gym with scheduled exercise may also help motivate the patient.

Patients who do follow an exercise program may rarely exhibit hypoglycemia either during or immediately after exercise; they may also have a delayed hypoglycemic response many hours or even a full day following active exercise. Encourage your patients to:

•Check their blood glucose level before they start to exercise.

•Ingest adequate amounts of carbohydrate before exercise.

•Stay alert to the possibility of hypoglycemia after exercise (either immediately or hours later).

OVERINSULINIZATION

3 Most insulin recipients who are evaluated for poor blood glucose control (ie, those with marked “glucose bounces”) are usually receiving too high a dose of insulin. This may lead to recurrent hypoglycemic episodes, many of which may result in significant neuroglycopenic symptoms. If the autonomic nervous system is intact, there is an increased release of counterregulatory hormones (such as adrenocorticotropic hormone [ACTH], cortisol, glucagon, and growth hormone) that cause a “rebound” phenomenon.

However, patients who are sensitive to even relatively slight falls in blood glucose levels may experience repeated episodes of neuroglycopenic symptoms. Because they fear hypoglycemic reactions, these patients may eat excessively to compensate. This can result not only in subsequent rises in blood glucose levels but also in weight gain.

In our desire to control glucose levels with minimal amounts of medication, we often overlook the fact that in type 2 diabetes mellitus, insulin is secreted by the pancreas throughout the day in a basal secretory state. When the pancreas is challenged by increased amounts of carbohydrates, insulin secretion is stimulated. It would seem that 1 or even 2 injections of intermediate- and short-acting insulin—either by themselves or in combination—cannot duplicate the complex pattern of insulin secretion seen in a nondiabetic person over 24 hours. Even the popular 2-dose insulin injection regimen may be unsuccessful.

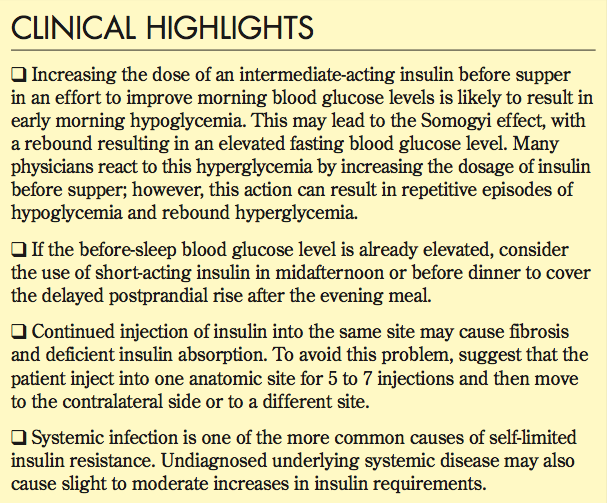

Increasing the dose of an intermediate-acting insulin before supper in an effort to improve morning blood glucose levels is more likely to cause hypoglycemia at the peak time of its effect (6 to 8 hours) and to result in early morning hypoglycemia. This may lead to the Somogyi effect, with a rebound resulting in an elevated fasting blood glucose level. Many physicians react to this hyperglycemia by increasing the dosage of insulin before supper; however, this action can result in repetitive episodes of hypoglycemia and rebound hyperglycemia.

It is probably necessary to initiate injections of insulin at the hour of sleep, such as insulin glargine or mixtures of long- and short-acting insulin. If the before-sleep blood glucose level is already elevated, consider the use of short-acting insulin in midafternoon or before dinner to cover the delayed postprandial rise after the evening meal.

INADEQUATE PATIENT EDUCATION

4 The importance of education. Every person with diabetes needs to be educated about his or her disease. For example, despite the relative simplicity of using an insulin syringe, a lack of satisfactory guidance may produce anomalous clinical results—even in the mature or so-called educated patient with diabetes. Common problems include failure to mix the insulin vial or pen thoroughly: the result may be an inadequate hypoglycemic effect when starting a new vial and severe, repetitive hypoglycemic reactions as insulin from the bottom of the vial is aspirated into the syringe. Instruct patients to inspect their insulin preparations carefully before each use. Any change (ie, clumping, precipitation, frosting, or altered clarity) may indicate a loss of potency and/or possible contamination.

A common problem with glucose monitoring is “tender fingertip syndrome,” secondary to repeated finger sticks. Advise patients to adjust the depth of penetration of the needle of the lancing device. Fingers 3 to 5 should be specified for use. Encourage the use of a new lancet every time the glucose is checked. If the fingertips are too painful, consider alternative sites, such as the arm or thigh.

Possible confounding problems that lead to medication errors. Make sure the patient has adequate visual acuity: poor vision frequently leads to serious errors, such as the administration of inadequate or excessive insulin doses. A magnifying lens can be attached to the syringe to help prevent this complication.

Many mistakes are also made during the administration of oral antidiabetic medications. In many managed pharmacy plans, generic preparations are often provided instead of trade name medications: this can generate confusion, since many patients—particularly older ones—do not know the names of generic preparations. Some who use multiple pharmacies may be taking agents with the same chemical structure and believe that they are receiving different medications.

Patients may also neglect to take medications because of their cost or because of feared or actual adverse effects. Almost all patients now review package inserts, and many heed the warnings appended to the vials of medication by the pharmacist. Because of potential adverse effects listed in the package insert and on medication vials, the patient may decide to discontinue his medication without informing you. Also, “downsizing” of insurance pharmacy plans may also prompt patients to stop taking their medications. You must specifically ask each patient whether he is taking the medication as directed, or diabetic control may go awry.

Miscommunication and polypharmacy. Ethnic diversity among patients in many medical practices complicates communication. Even English-speaking persons with diabetes and coexisting illnesses may have complications associated with polypharmacy, from, for example, antidiabetic agents, antihypertensive medication, anticoagulants, vitamins, etc.

Nonemergency prescriptions. There is also the recent unfortunate tendency for patients, drug management representatives, and pharmacists to phone physicians during off-duty hours for prescription renewals. Patients may be confused by a medication’s name, color, size, or dosage. The physician may also err if he or she cannot corroborate the dosage by referring to the patient’s records.

One obvious alternative is to keep a medication sheet up to date in the patient’s chart. Another precaution (albeit one that may be unpopular with patients) is to ban the filling of nonemergency prescriptions by telephone. Physicians can, on request, mail prescriptions after referring directly to the patient’s records.

A meticulous review of medications is important during every office visit. It may be prudent to supply the patient with his own list of medications, which can be kept up to date by the patient or office assistants. The patient can carry this list, with the correct dosages, on a small card in a wallet or handbag; it will then be available for checking by a physician or a pharmacist.

DIFFICULTIES WITH INSULIN INJECTION SITES

5 Studies that are carefully controlled for a variety of factors that influence diabetic control (such as insulin administration, diet, and physical activity) show considerable variability in blood glucose levels. Multiple studies indicate that the rate of absorption of insulin from subcutaneous injection sites varies from patient to patient; the rate also varies depending on the injection site. Insulin appears to be most rapidly absorbed (in descending order) from the abdomen, arms, thighs, and buttocks. These differences are probably related to variations in blood flow.

Patients are generally instructed to avoid injections in the upper abdomen (above the level of the umbilicus). However, one often finds that because of hurried injection or deficient attention, there may be extensive ecchymoses in the upper abdominal skin as well as local tender areas in the thighs or abdomen from repeated injections. Many patients have discovered their own “preferred sites” where the skin is less sensitive to needle sticks, possibly because of a sensory neuropathy. Unfortunately, continued injection into the same site may cause fibrosis and deficient insulin absorption. To avoid this problem, you might suggest that a patient inject insulin into one anatomic area for 5 to 7 injections and then move to the contralateral side or to a different area.

Many patients find insulin pens convenient and prefer to use them. Despite instructions, however, many patients do not initially use an “air shot” when they start a new ampule of insulin. Similarly, those who employ regular insulin syringes often fail to eject the bubble of air from the syringe to help ensure accurate dosing. Many patients also fail to adequately mix their insulin vials or their insulin pen before use.

This problem can be avoided if you advise the patient to flick the insulin pen or vial 10 to 20 times before use. Failure to do so will result in imprecise dosing.

Also advise your patients not to expose their insulin to excessive heat or cold. Freezing of insulin inactivates the drug and is therefore to be avoided, as is exposure of insulin to high temperatures. Remind your patient that insulin pen cartridges can be kept at room temperature for 10 days without a loss of drug potency.

It is well worth your time to periodically review with your patients the selection of injection sites and the mechanics of insulin injection.

The use of continuous subcutaneous insulin (ie, pump therapy) as an alternative to frequent injections is being accepted in young patients and selected adults with type 1 diabetes. Because of the expense and the need for a high degree of patient and health care provider training, its use remains controversial and limited. It is not recommended for most adults with type 1 diabetes or for patients with type 2 diabetes.

UNSTABLE INSULIN LEVELS

6 Clearly, insulin levels do not remain stable during the day. Glucose levels rise after carbohydrate feeding, during emotional stress, and after taking other medications—such as diuretics, corticosteroids, anticonvulsants, or thyroid replacement therapy.

In addition, patient responses may vary a great deal after administration of intermediate-acting insulin. For example, at least three different patterns (ie, “A,” “B,” and “C” curves) for intermediate-acting insulin have been described. Peak insulin activity occurs earlier in the type A curve and is somewhat delayed in the type C curve. Therefore, after the same dose of insulin, some patients may experience a maximum effect different from that experienced by the majority of patients. This can, of course, result in anomalies of control unless you specifically seek out and address the cause—and adjust the insulin dosage accordingly.

TRUE INSULIN RESISTANCE

7 Insulin resistance may be defined as an insulin requirement in excess of 200 units per day. This syndrome can be caused by anti-insulin antibodies; however, it is uncommon, since animal insulin sources have been replaced by cloned human insulin and by truly synthetic insulin. Nevertheless, there are still some rare reports of persons who demonstrate extreme resistance.

Various endocrine disorders—including hyperthyroidism, Cushing syndrome, pheochromocytoma, and acromegaly—and acute and chronic administration of corticosteroids can trigger a transient or permanent need for a higher insulin dosage. Injection of intra-articular or intrathecal corticosteroids or use of corticosteroids over a large area of skin can significantly elevate glucose levels. Various diuretics (ie, thiazides) can cause hypokalemia and trigger an apparent need for increased insulin. Similarly, sympathomimetic agents used to combat allergy and upper respiratory tract infection may cause a temporary need for increased insulin dosage.

Bear in mind that systemic infection, which may occur in prodromal fashion without actual symptoms, is one of the more common causes of self-limited insulin resistance. You may find an increased need for insulin even while the patient is incubating a viral or bacterial disorder. Undiagnosed underlying systemic disease (eg, cancer or collagen vascular or inflammatory disorders) may also cause slight to moderate increases in insulin requirements.

It has been recognized for some time that there is a certain group of disorders comprising obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and atherosclerosis. Metabolic studies have demonstrated insulin resistance and compensatory hyperinsulinemia: the insulin-resistance syndrome, CHAOS (coronary artery disease, hypertension, adult-onset diabetes, obesity, and stroke).

Insulin resistance has also been described with the metabolic syndrome; polycystic ovary syndrome, a relatively common condition involving chronic anovulation and hyperandrogenism; and acanthosis nigricans.

Causation of marked insulin resistance may result from abnormalities with insulin receptors, altered production of proinsulin, insulin antibodies, or altered insulin degradation. A huge insulin dosage requirement may result. Patients may require insulin with a concentrated dosage, ie, U500 insulin instead of U100; U500 is available as a regular form of insulin from Eli Lilly.

FEAR OF SEVERE HYPOGLYCEMIC REACTIONS

8 It is not unusual for patients who experience repeated hypoglycemic episodes (ranging from mild symptoms of neuroglycopenia to those requiring a “911” call) to overreact to even minor symptoms of hypoglycemia. This sensitivity may result in large nocturnal carbohydrate intake; the result is an elevation of morning fasting blood glucose levels. This may lead to the need for an increase in insulin dosage, perpetuation of repeated hypoglycemic symptoms, and overeating.

Encourage your patients to keep their glucose tablets with them at all times (either on their person or in their car, by their bed, or in the kitchen, bathroom, or den). Consumption of several of these pills usually relieves hypoglycemic symptoms promptly without the need for overcorrection. Glucose tablets may prevent patients from making nocturnal visits to the refrigerator where they overconsume high-carbohydrate foods.

COEXISTING GI DISORDERS

9 Dysphagia and abnormalities in esophageal and gastric motility are common among patients who have autonomic neuropathy secondary to long-standing diabetes. Gastroparesis can be a difficult clinical problem because the stomach empties so erratically. The usual presentation is that of either hyperglycemia or, more frequently, hypoglycemia secondary to delayed food absorption. Certainly, the patient who has had insulin-requiring diabetes for more than 10 years and who has erratic blood glucose bounces should be investigated for the GI manifestations of autonomic neuropathy.

Chronic ethanol intake with underlying chronic hepatitis, hepatic cirrhosis, and/or accompanying pancreatitis may cause extreme instability with frequent, poorly controlled hyperglycemia and/or life-endangering hypoglycemia with coma.

PSYCHOLOGICAL ISSUES

10 Eating disorders. Eating is a complex process with deep psychological and emotional overtones. Psychological factors may contribute to pathological eating habits and a loss of diabetic stability.

Patients with diabetes may attempt to control their weight by omitting or reducing their insulin dosage. This usually results in polyuria, glycosuria, and hyperglycemia.

The prevalence of eating disorders among persons with insulin-dependent diabetes is apparently greater than among persons without diabetes. Adolescent reaction to restriction of food and caloric intake is frequently displayed as dietary nonadherence and consumption of high-carbohydrate “junk foods,” especially when the patient is not eating at home and is unsupervised. When weight loss, electrolyte imbalance, manipulation of insulin dosage, and dissatisfaction with body appearance and weight become evident, referral to a mental health team for specific treatment is indicated.

Depression. Abnormalities of glucose control that cause recurrent hypoglycemia can be a symptom of depression. Although depression is not usually listed as a diabetic complication, it may have dangerous consequences if untreated. The rate of major depression in persons with diabetes is greater than that in the general population. Depressed patients are at greater risk for repeated episodes of hypoglycemia. Depression is frequently associated with changes in appetite, and the depressed patient may not be motivated to maintain good diabetic control. Depression is common following the diagnosis of diabetes, which is considered to be a major stressor, and anger is also quite common. Patients may display decreased pleasure in normal activities, change in sleeping patterns, depressed mood, weight loss or weight gain, difficulty in concentrating and, in severe cases, suicidal ideation.

Prompt diagnosis of this diabetic complication is necessary. A number of antidepressant agents are available, ranging from tricyclic antidepressants (which do not appear to worsen diabetic control in depressed persons) to the selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (often used as first-line antidepressants).

Anxiety disorders. Other psychiatric disorders that may upset diabetic patients’ metabolic balance include various types of anxiety disorders, such as panic disorders as well as specific phobias and obsessive-compulsive disorder. It is important to diagnose and treat these disorders, since both anxiety and stress can cause catecholamine elevation with resulting significant jumps in blood glucose levels. Panic attacks may actually resemble hypoglycemic episodes and vice versa with disorientation, tachycardia, sweating, feelings of unreality, etc.

Caution your patients with such disorders to check their blood glucose levels frequently to be sure that their symptoms are caused by panic symptoms rather than neuroglycopenia. Encourage them to take as active a role in their psychological care as they do in their diabetic care.

OVERLOOKING AN ISLET CELL TUMOR

11 The occurrence of severe hypoglycemia at odd times without any apparent reason (such as a change in pattern of food intake or alterations in dosages of oral agents or insulin) suggests an endogenous source of insulin. The physician must explore this possibility as well as that of iatrogenic administration of oral agents or insulin by an emotionally unstable patient. Nevertheless, evaluation of hyperinsulinemia with measurement of fasting insulin levels and C-peptide levels may indicate the presence of an underlying pancreatic islet cell tumor. A careful workup that includes a detailed history, complete physical examination, measurement of hormonal levels, abdominal CT scans, and octreotide scanning is necessary to rule out underlying pathology.

PROBLEMS WITH BARIATRIC SURGERY

PROBLEMS WITH BARIATRIC SURGERY

12 When diets and insulin and/or oral agents are no longer effective in the obese patient with diabetes, patients and physicians alike consider bariatric surgery. Once the procedure is performed, however, problems do not disappear. Although evidence exists that bariatric surgery can induce durable weight loss with long-term remission of type 2 diabetes, and alleviation of other comorbidities, many problems result. These include iron deficiency, hypovitaminosis C, D, K, B12, folate, and thiamine, as well as numerous GI hormones.

Despite excellent responses (ie, improvement or “disappearance” of diabetes), typically hyperglycemia may return in a year. Other problems include hypoglycemia, dumping syndrome, neuropathy, and diminished bone health. Physicians considering this form of therapy need to be cognizant of possible problems when advising their patients with diabetes.

HELP IS AVAILABLE

Even if patients are educated about their disease and are relatively “healthy,” the management of diabetes can be difficult and frustrating. Consultation with a diabetologist or an endocrinologist can offer insights into the challenging problems of glycemic control.

FOR MORE INFORMATION:

- American Diabetes Association. Insulin administration. Diabetes Care. 1997;(suppl 1):S46-S49.

- Bantle JP. Injection site rotation: the down side. Practical Diabetology. 1990;9:1-3.

- Birk RS. Psychological issues of eating dysfunction and diabetes. Practical Diabetology. 1990;9:12-13.

- Davidson MB. Clinical implications of insulin resistance syndromes. Am J Med. 1995;99:420-425.

- Rubin RR, Peyrot M. Psychosocial problems in diabetes treatment. Practical Diabetology. 1994;13:8-14.

- Watkins CD. Depression and anxiety in the person with diabetes. Practical Diabetology. 1998;17:16-20.

- Psychosocial aspects of diabetes in adult populations. In: Diabetes in America. 2nd ed. Bethesda, Md: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 1995:507-517.