Peer Reviewed

An Atlas of Nail Disorders, Part 1

Alexander K. C. Leung, MD

Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, University of Calgary; Pediatric Consultant, Alberta Children’s Hospital, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Benjamin Barankin, MD

Dermatologist, Medical Director and Founder, Toronto Dermatology Centre, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Kin Fon Leong, MD

Pediatric Dermatologist, Pediatric Institute, Kuala Lumpur General Hospital, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

CITATION:

Leung AKC, Barankin B, Leong KF. An atlas of nail disorders, part 1. Consultant. 2019;59(11):334-336.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article is part 1 of a 15-part series of Photo Essays describing and differentiating conditions affecting the nails. Parts 2 through 15 will be published in upcoming issues of Consultant.

Onychocryptosis (Ingrown Toenail)

Onychocryptosis, also known as an ingrown toenail or unguis incarnatus, is a common form of nail disease in adolescents and young adults.1 The word onychocryptosis is derived from the Greek words onyx, meaning “nail,” and kryptos, meaning “hidden.” The male to female ratio is approximately 2 to 1.2 The condition is unilateral in approximately 80% of cases.3 Onychocryptosis results from penetration, most often caused by spicules of nail at the edge of the nail plate, into the periungual skin resulting in an inflammatory foreign-body reaction.1 Improper trimming of the nail (in a half circle rather than straight across), pressure from tight shoes, repetitive trauma to the toe (eg, kicking, running), inadvertent injury to the nail, hyperhidrosis, and reduced capability to care for one’s nails may contribute to its formation.2-4

The medial and lateral borders of the great toe are most commonly affected.1,4 The affected nail fold becomes erythematous, edematous, tender, and hypertrophic as the nail grows into the neighboring soft tissue (Figure 1). The condition is exquisitely painful, especially if pressure is applied to the affected area.5 Secondary bacterial infection with seropurulent discharge, paronychia, and formation of granulation tissue typically ensue (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Figure 2.

If left untreated, onychocryptosis may result in a progressively more painful digit, which may affect an individual’s functional ability such as walking and participation in sports.4 The condition may have an adverse effect on quality of life.3 Conservative treatment includes wearing properly fitting shoes, avoidance of overzealous nail trimming, soaking the affected toe in warm water followed by the application of topical antibiotic and/or corticosteroid, elevation of the nail edge by placing wisps of dental floss or cotton under the ingrown nail edge, and applying a gutter splint to the ingrown nail edge.1,2,5 Systemic antibiotics with gram-positive coverage should be considered for severe secondary bacterial infection.2 Wedge resection/avulsion of the involved nail border, including the nail matrix, may be necessary if conservative measures fail or when the condition is extremely painful or recurrent.2,6 Partial ablation of the geminal nail matrix (matricectomy) can be used to prevent recurrence and can be performed with surgical excision, chemicals (eg, phenol, sodium hydroxide), electrocautery, or carbon dioxide laser ablation.2,4,6,7

REFERENCES:

- Khunger N, Kandhari R. Ingrown toenails. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78(3):279-289.

- Ezekian B, Englum BR, Gilmore BF, Kim J, Leraas HJ, Rice HE. Onychocryptosis in the pediatric patient: review and management techniques. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2017;56(2):109-114.

- Borges APP, Pelafsky VPC, Miot LDB, Miot HA. Quality of life with ingrown toenails: a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43(5):751-753.

- Mayeaux EJ Jr, Carter C, Murphy TE. Ingrown toenail management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(3):158-164.

- Gera SK, PG Zaini DKH, Wang S, Abdul Rahaman SHB, Chia RF, Lim KBL. Ingrowing toenails in children and adolescents: is nail avulsion superior to nonoperative treatment? Singapore Med J. 2019;60(2):94-96.

- Richert B. Surgical management of ingrown toenails—an update overdue. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25(6):498-509.

- Bryant A, Knox A. Ingrown toenails: the role of the GP. Aust Fam Physician. 2015;44(3):102-105.

Paronychia

Paronychia (also known as perionychia), an inflammatory reaction involving the nail folds, can be classified as acute (less than 6 weeks’ duration) or chronic (6 weeks’ duration or longer).1 Acute paronychia is a painful inflammation of the folds of tissue surrounding the fingernail or toenail, with or without abscess formation. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common causative organism, followed by Streptococcus pyogenes.2,3 Other organisms that may be occasionally involved include Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus vulgaris, Eikenella corrodens, Fusobacterium, and Enterococcus.2,3 Herpes simplex virus and Candida albicans may also be involved.3

Trauma that facilitates entry of the organism into the paronychial tissue may result from a splinter or thorn, overzealous manicuring and cuticle damage, finger sucking, nail biting, ingrown nail, artificial nail, nail biting, or picking at a hangnail.3 Other predisposing factors include immunosuppression (eg, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, HIV infection) and occupations in which the hands or feet are frequently immersed in water (eg, homemakers, hairdressers, dishwashers, bartenders).4,5 The female to male ratio is approximately 3 to 1.2,4

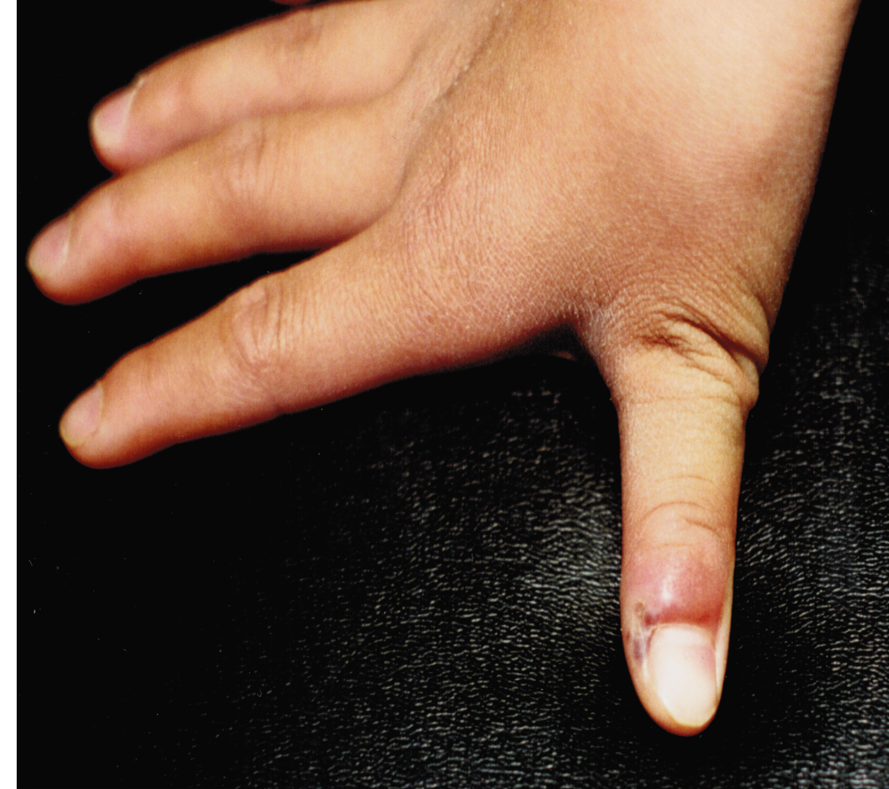

Clinically, the condition is characterized by acute onset of throbbing pain, erythema, edema, and tenderness in the proximal and lateral portions of the nail bed (Figure 1), usually within a few days after a local minor trauma.2,5 Usually, only one nail is involved, and the fingernail is affected more often than the toenail.2 Occasionally, the infection may spread along the proximal nail fold to the other side of the nail, resulting in the so called runaround infection.1 An area of fluctuance indicates the presence of an abscess. The digital pressure test, performed by asking the patient to oppose the thumb and the affected finger, thereby applying light pressure to the distal volar aspect of the affected finger, is useful in the early stage of infection to determine the presence and extent of an abscess.2 An increase in pressure within the paronychium causes blanching of the overlying skin and clear demarcation of the abscess.2

Figure 1.

The diagnosis of acute paronychia is mainly clinical and is based on a history of local trauma and typical findings on physical examination. Laboratory tests are usually not necessary.

If acute paronychia is not properly treated, it can lead to formation of granulation tissue around the nail fold, cellulitis, felon, ischemic necrosis of the fingertip, osteomyelitis, Beau lines, onychomadesis, and nail dystrophy.1 Acute paronychia can be treated with warm soaks with antiseptics (eg, povidone-iodine, chlorhexidine) or water, and topical antibiotics (eg, fusidic acid, mupirocin) with or without topical corticosteroids.2,5 Acetaminophen or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug may be used for symptomatic relief of pain. The routine use of oral antibiotics is controversial.1 Severe cases or cases not responding to topical antibiotic treatment might require the use of oral antibiotic therapy (clindamycin, flucloxacillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, doxycycline).3,5 Once an abscess has developed, incision and drainage is necessary.3 Infiltrative anesthesia or a wing block is preferred to a digital block to ensure comfort and complete drainage of the abscess.2,4 For prophylaxis, patients should be advised to avoid trauma to the paronychial folds and cuticle by trimming back hangnails with fine scissors.

Chronic paronychia usually involves multiple digits.2 Clinically, chronic paronychia presents with chronic mild erythema and edema of the proximal nail fold without fluctuance and disappearance of the cuticle (Figure 2).3 With time, the nail folds become hypertrophic, followed by marked retraction of the proximal nail fold. The nail plate may become thickened, discolored, or dystrophic.3,4 Pitting, Beau lines, longitudinal grooving, and onychomadesis may be present due to inflammation of the nail matrix.1,6 The diagnosis is mainly clinical, based on a history of chronic exposure to moisture and irritants and the characteristic physical findings.

Figure 2.

The etiology of chronic paronychia is multifactorial.6 Chronic paronychia may be caused by Candida species, pseudomonas (suggested by a discolored green nail bed as is shown in Figure 3), and streptococci.4 Although Candida species are the most frequently cultured microorganism in patients with chronic paronychia, some authors suggest that hypersensitivity to Candida species is more likely to be the etiology, rather than the infection itself.7 Chronic paronychia may also be caused by frequent exposure of the digit to moisture (such as finger sucking) and irritants.6 The condition may follow the use of certain medications such as retinoids, protease inhibitors, chemotherapeutic agents, and antiretrovirals.2,6 Chronic paronychia is more common in individuals with inflammatory skin diseases (eg, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis) and individuals with immunosuppression (eg, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, HIV infection).2

Figure 3.

Treatment is directed at the underlying cause, such as avoiding exposure of the digit to moisture and irritants and wearing gloves while performing work with probable exposure to moisture and irritants. Offending medication should be discontinued. The use of topical corticosteroids or calcineurin inhibitors is the first-line therapy.1,2,5,6 Topical or systemic antifungal agents (eg, terbinafine, itraconazole, fluconazole) may be considered if Candida infection is suspected. Chronic paronychia may recur in susceptible individuals.4 In recalcitrant cases, en bloc excision of the proximal nail fold or an eponychial marsupialization, with or without removal of the nail plate, should be considered.6

REFERENCES:

- Goldstein BG, Goldstein AO, Tosti A. Paronychia. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/paronychia. Updated July 29, 2019. Accessed October 28, 2019.

- Leggit JC. Acute and chronic paronychia. Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(1):44-51.

- Lomax A, Thornton J, Singh D. Toenail paronychia. Foot Ankle Surg. 2016;22(4):219-223.

- Dulski A, Edwards CW. Paronychia. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544307/. Updated September 12, 2019. Accessed October 28, 2019.

- Shafritz AB, Coppage JM. Acute and chronic paronychia of the hand. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2014;22(3):165-174.

- Relhan V, Goel K, Bansal S, Garg VK. Management of chronic paronychia. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(1):15-20.

- Bahunuthula RK, Thappa DM, Kumari R, Singh R, Munisamy M, Parija SC. Evaluation of role of Candida in patients with chronic paronychia. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2015;81(5):485-490.