Rashes and Fever in Children: Sorting Out the Potentially Dangerous, Part 4

William A. Gibson, MD

Brooke Army Medical Center San Antonio, Texas

Citation:

Gibson WA. Rashes and fever in children: sorting out the potentially dangerous, part 1. Consultant Pediatr. 2010;7(4)160-163.

ABSTRACT: Most children with early or undifferentiated rash and fever have benign viral illnesses. However, the possibility of serious diseases must be ruled out. Thus, children who present with early or undifferentiated rash and fever may require further evaluation by appropriate specialists, and all require close follow-up. The distribution of the rash—whether central or peripheral—may be a clue to diagnosis. For example, lesions associated with varicella, Kawasaki disease, erythema multiforme, and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome are initially located on or near the trunk. In some children, travel history may provide clues: some diseases are limited to certain regions of the country. Still other clues may be provided by the season (many illnesses peak at a specific time of year); the timing and pattern of the fever (eg, late afternoon or evening, early morning, recurring); or the presence of another key symptom, such as arthritis.

The sudden onset of rash and fever in a child frequently causes anxiety in parents. Fortunately, their worries are usually for naught. Most children who present with a rash and fever have a benign viral illness (whether or not it is easily identified). However, rash and fever can be the presenting signs of serious illness. Thus, it is vitally important in this setting that pediatricians be able to quickly review the differential diagnosis and determine whether a serious disease is likely.

In the previous 3 articles in this series (Part 1; Part 2; Part 3), I presented a triage system that can help clinicians quickly narrow the diagnostic possibilities and assess the likelihood of potentially serious illness. This system involves categorizing the patient's presenting symptoms into 1 of 3 groups:

• Group 1 includes children with symptoms of serious illness who require immediate intervention.

• Group 2 includes children with a clearly recognizable—and usually benign—viral syndrome.

• Group 3 includes children who present early in the course of the disease, when the clinical picture and physical findings are nonspecific, and those with undifferentiated rashes with fever. (Most febrile children with rash fall into this group.)

In the earlier articles in this series, I focused on children in the first two of these groups: those who present in obvious need of prompt intervention or with an easily recognizable viral exanthem. Here the focus is on children in group 3: those who present with early or undifferentiated rashes and fever. I discuss several types of clues—such as the distribution of the rash, the part of the country in which the patient fell sick, and the season of the year—that can help in your efforts to establish a diagnosis and rule out serious conditions.

EARLY OR UNDIFFERENTIATED RASHES WITH FEVER: GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

The rashes associated with group 3 are the most perplexing of all. In children whose symptoms fall into group 1 or 2, the diagnosis is relatively straightforward. Those in group 3, however, lack some or most of the recognizable features of a specific disease. Differentiating between the potentially serious and the innocuous is extremely difficult. This is where you will earn your pay!

The vast majority of children with early or undifferentiated rashes and fever have benign viral illnesses that resolve spontaneously. Hidden among these, however, are the early and atypical presentations of the serious diseases discussed in earlier articles in this series. Thus, children in group 3 may require further evaluation and consultation with appropriate specialists.1 They also require close follow-up with good access to care. When there is concern about whether parents will be able to provide adequate care, it is sometimes necessary to admit the child.

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES THAT CAN HELP IN DIFFICULT CASES

Location of the rash. In many cases, the initial site and distribution of the rash may offer diagnostic clues (Table 1). For instance, lesions associated with varicella, Kawasaki disease (Figure 1), erythema multiforme, and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome are initially centrally located (ie, on or near the trunk), whereas the lesions of Rocky Mountain spotted fever and smallpox are initially peripheral (on the wrists and ankles, and on the face and extremities, respectively).

Figure 1. A diffuse erythematous maculopapular rash typically develops in children with Kawasaki disease within 3 days of the onset of fever. The rash occurs primarily on the trunk. (Photo courtesy of Abu Taher, MD)

Associated symptoms. Often, there is another symptom that can help narrow the differential diagnosis. For example, in adolescents who present with fever, rash, and arthritis, consider septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, and disseminated gonococcal disease; in children who present with fever, rash, and arthritis, consider rheumatic fever and juvenile rheumatoid arthritis.2

Conjunctival suffusion, or redness of the eyes unaccompanied by discharge, may be seen in patients with leptospirosis. Conjunctivitis is very common in children with Kawasaki disease. (It has been my observation that children with Kawasaki disease usually present with a nontoxic appearance but seem profoundly unhappy.)

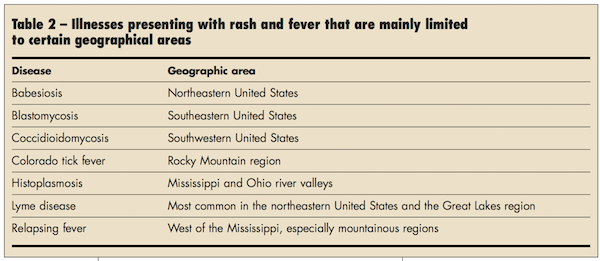

Travel history. Some diseases are limited mainly to specific regions of the country (Table 2). Lyme disease (Figure 2), for example, is exceedingly rare in Texas but is endemic in many areas of the Northeast. Rocky Mountain spotted fever occurs throughout Canada, the United States, Mexico, Central America, and northern portions of South America. In the United States, it is most common in the Southeast and South Central areas—ironically not in the Rocky Mountain area. The most recent CDC data show that North Carolina has had the largest number of reported cases.3

Figure 2. The characteristic rash of Lyme disease, erythema migrans, often has a bull's-eye appearance. Erythema migrans is seen in about 80% of patients with Lyme disease. (CDC/James Gathany)

Fever timing and pattern. While most fevers occur in the late afternoon and evening, typhoid fever tends to cause early morning fever.4 A fever that decreases over a few days only to return can herald a new viral infection or a bacterial complication (eg, sinusitis, otitis media, pneumonia) of an antecedent viral infection.

However, this intermittent fever pattern is also typical of leptospirosis, ehrlichiosis, and rat-bite fever. Both leptospirosis and ehrlichiosis cause similar clinical symptoms: intermittent high fevers, headache, body aches, nausea, vomiting, and a nonspecific macular or maculopapular rash (although rash may be absent in ehrlichiosis). Leptospirosis usually causes considerable redness of the eyes without discharge and may cause jaundice. Note that although a history of exposure to a rodent may raise suspicion for rat-bite fever, a child does not need to be bitten by a rat to contract the disease.5 Infected mice and gerbils can also spread rat-bite fever, as can the ingestion of food or drink contaminated by rat excrement. Definitive diagnosis requires laboratory testing.

A pattern of intermittent fevers can also be caused by cyclic neutropenia, juvenile lupus, osteomyelitis, and rare diseases such as hyperimmunoglobulinemia D syndrome.6 It is necessary to perform specific laboratory tests to establish the diagnosis for most of these disorders.

Intermittent fevers that last for more than 3 weeks are categorized as fever of unknown origin. These usually result from infections, systemic inflammatory diseases, and neoplastic disorders.

Season of the year. Many illnesses peak during certain seasons. Enteroviral diseases, meningococcal disease, and Kawasaki syndrome are frequently seen in the winter and early spring. Rubella and measles tend to occur later in the spring. Tick-borne illnesses occur most commonly in the late spring and summer months.

Medication history. Is the child taking any medications? The combination of fever and rash as a medication reaction is rare, but it has been seen with the use of multiple antibiotics and with antihistamines, anticonvulsants, and antipyretics—including acetaminophen and ibuprofen. Drug fevers can occur at any time while a patient is taking a medication; they tend to resolve within 48 hours of discontinuation.7

REFERENCES:

1. Cunha BA. Fever of unknown origin: clinical overview of classic and current concepts [published correction appears in Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2008;22:xv]. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007;21:867-915, vii.

2. Brokaw FC. Fever, rash and polyarthralgias. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(suppl 1):38.

3. Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention. Summary of provisional cases of selected notifiable diseases, United States, cumulative, week ending December 18, 2004 (50th week). MMWR. 2004;53:1185-1193.

4. Tolia J, Smith LG. Fever of unknown origin: historical and physical clues to making the diagnosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007;21:917-936, viii.

5. Albedwawi S, LeBlanc C, Shaw A, Slinger RW. A teenager with fever, rash, and arthritis. CMAJ. 2006;175:354.

6. Padeh H. Periodic fever syndromes. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005;52:577-609.

7. Johnson DH, Cunha BA. Drug fever. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1996;10:85-91.