Marijuana Cessation Screening and Counseling for Young Adults in the Primary Care Office

AUTHOR:

She Zhao, FNP-BC

CITATION:

Zhao S. Marijuana cessation screening and counseling for young adults in the primary care office. Consultant. 2015;55(3):172-178.

ABSTRACT: Marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug in the United States. More than a dozen states are expected to consider proposed laws to legalize or expand access to medical marijuana. While the primary care screening tools for alcohol and tobacco exist, there is currently nothing specific for marijuana use. Marijuana cessation, however, has often been handled by mental health providers or in treatment programs. Given the adverse outcomes with marijuana use at a young age, it is critical for primary care providers (PCPs) to capture high-risk patients and perform brief in-office interventions. This article provides PCPs with valuable insights on adolescent marijuana use, as well as results from a pilot study that discussed strategies for conducting brief in-office screenings and cessation counseling.

The 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that marijuana is the most commonly used illicit drug (19.8 million past-month users).1 Shifts in government policy both at the state and federal level, as well as in public opinion regarding its toxicity compared to alcohol continue to spark debate over just how benign marijuana is. Between now and 2016, more than a dozen states are expected to consider proposed laws to legalize or expand access to medical marijuana, an increasing acceptance level that is spurring heightened concern among parents, educators, and substance abuse counselors who worry that marijuana’s harmful side effects are being overlooked particularly by teens.2 Not only are more states considering varying degrees of decriminalization, there is a growing call for Congress to reclassify this botanical drug as a Schedule II drug—the same classification as cocaine and methamphetamine3—further broadening its accessibility. The number of teens using marijuana seems to be fluid, but experts’ position on its cognitive and behavioral impact remains firm. Momentum is clearly on the side of marijuana gentrification, however, elevating concerns about the message being sent to adolescents, for whom marijuana is the most popular illicit drug.4

By the Numbers

Marijuana use is widespread among adolescents and young adults. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, in 2013, 7.0% of 8th graders, 18.0% of 10th graders, and 22.7% of 12th graders used marijuana in the past month, up from 5.8%, 13.8%, and 19.4%, respectively, in 2008. Daily use has also increased—6.5% of 12th graders now use marijuana every day, compared to 5% in the mid-2000s. These numbers are slightly off from 2014’s Monitoring the Future Survey of drug use and attitudes among American 8th, 10th, and 12th graders, which shows “stable” rates of marijuana use among teens and no significant difference in the rates of marijuana use among high school seniors in medical marijuana states versus nonmedical marijuana states (34.5% - 30.1%).5 This is in contrast to 2013 when 40.4% of high school seniors in medical marijuana states reported smoking marijuana in the past year compared to 29.7% in nonmedical marijuana states.

Contrarily, alcohol and tobacco use in adolescents has been decreasing over the past several years,6 also noted in the Monitoring the Future survey.

Demographically, New York City, where marijuana is the most misused drug, showed its highest use among those age 18 to 25 years old.7 Additionally, numerous research studies substantiate marijuana’s addictive properties and increased addiction for all age groups. Teens are using at younger ages, with 1 out of every 6 developing an addiction. Concurrently, findings show that half the people who receive treatment for marijuana use are under the age of 25.8

Evolving attitudes about the perceived risk of harm associated with marijuana use, along with growing decriminalization efforts, have parents and educators worried, making it imperative for primary care providers to take a more active role in marijuana screening and counseling. A 2014 study published in the International Journal of Drug Policylooked at the relationship between behavior and legalization, and found that 10% of high school students who would otherwise be at a low risk for picking up a pot-smoking habit—which includes those who do not smoke cigarettes, students with strong religious beliefs and those with nonmarijuana smoking friends—said they would use marijuana if it was legal.9

Stephen Ross, MD, director of addiction psychiatry at NYU Tisch Hospital in New York, reiterated this message during an interview with CBS medical correspondent and professor at NYU Langone Medical Center, Jonathan LaPook, MD.10

"We know that in high school students, perception of harm is very much correlated with use. If high school students think something is harmful they're much less likely to use it, and the converse is very much the case."

PCPs Role in Identifying At-Risk Teens

Though accessibility, perception and consumption continue to be under scrutiny, evidence strongly suggests that early use of cannabis is associated with an increased risk of adverse developmental outcomes,11 requiring PCPs to establish greater transparency with their adolescent patients—and to deliver a more informed and impactful message.

For clinicians with limited cannabis experience, it is first necessary to understand its physical and chemical characteristics. Botanically, marijuana is derived from the hemp plant Cannabis sativa. A mixture of dried, shredded leaves, stems, seeds, and flowers,12 it is most commonly inhaled via cigarettes, cigars, pipes, water pipes, or “blunts,” and its oil base can also be mixed into food products and teas. Therapeutically, medical marijuana and other cannaboids may relieve clinical symptoms associated with glaucoma, nausea, AIDS-associated anorexia/wasting syndrome, chronic pain, inflammation, multiple sclerosis and epilepsy.13 While not approved by the FDA, medical marijuana is currently legal in 23 states plus Washington, DC; recreational marijuana in 2 with Alaska and Oregon going legal in 2016 and Vermont likely not far behind.14,15

Among roughly 500 compounds found in cannibas, 70 of them are psychoactive.16 Of these, delta-9-tetrahydrocnnabinol (THC) is the main active ingredient and causes many of the psychoactive effects of marijuana use.17 THC resembles a naturally occurring brain chemical, anandamide, which binds to cannabinoid receptors.12 This neural communication network, named the endocannabinoid system, plays a crucial role in normal brain development and function: THC's similar structure allows it to be recognized by these receptors and to transform normal brain communication, creating the "high" sensation. This may include altered perception or mood, impaired coordination, difficulty with thinking, and disrupted learning and memory. When researchers discuss the potency of marijuana, they typically are measuring the concentration of THC.16 The level of THC in a plant varies based on the strain. THC levels also differ depending on the part of the plant used, and how it is processed for consumption.

Though public perception is that marijuana is a harmless drug, research is showing it can have a damaging impact on developing brains and may lead to lifelong addiction.2 Many consumers of marijuana and the general public assume that marijuana is safer to use than tobacco and other illicit substances due to its legality in some states. However, a review in the New England Journal of Medicine suggests that marijuana use can adversely affect health and other psychosocial components. These effects are especially damaging to adolescents and young people impairing brain development, memory, coordination, and school performance.13

Increased potency is also a concern: In 2012, the average concentration of THC in marijuana was 15% (compared to just 4% in the 1980s).18 The University of Mississippi Potency Monitoring Project, which analyzed tens of thousands of marijuana samples confiscated by state and federal law enforcement agencies since 1972, found that the average potency of all seized cannabis has increased from a concentration of 3.4% in 1993 to about 8.8% in 2008. Potency in sinsemilla in particular has jumped from 5.8% to 13.4% during that same time period.16

Neurological Effects

Heavy marijuana use in adolescence affects brain development by impairing neural connectivity and decreasing neuronal activity. Brain development spans from prenatal to about 21 years of age, so the immature brain is more vulnerable to adverse effects of THC exposure.19 Imaging studies in those who used cannabis regularly as adolescents showed decreased activity in prefrontal regions and reduced volumes in the hippocampus.20 Binding of THC receptors in the hippocampus also impairs the ability to form new memories and shift focus. Additionally, THC binds to receptors in the cerebellum and basal ganglion disrupting coordination, balance, and reaction time.21

These brain changes subsequently impair coordination, driving, athletics, and problem solving.17 These impediments adversely affect school performance and can lead to lower life satisfaction. Researchers found an 8 point IQ drop in those who smoked heavily between age 13 to 38 years compared to those who started smoking marijuana in adulthood.22 Compared with nonsmoking peers, students who smoke marijuana tend to get lower grades and are more likely to drop out of high school.23 Overall, the majority of marijuana users self-reported negative effects on their cognitive abilities, career achievements, social lives, and physical and mental health.24

Additionally, recent findings link narcolepsy in teens—specifically excessive daytime sleepiness and abnormal rapid eye movement sleep patterns.25 The study found that more than 40% of adolescents whose urine tested positive for marijuana have symptoms consistent with narcolepsy. Another study published in the Journal of Neuroscience concluded that there was a strong relationship with age at first use—regardless of frequency—and sleep problems as an adult.25

Other Side Effects

Regular marijuana use can also lead to respiratory problems and sexual dysfunction. According to the American Lung Association, marijuana smoke contains 33 cancer-causing materials. Smoking marijuana deposits 4 times as much tar into the lungs as smoking equal amounts of tobacco. This is because joints are unfiltered and often more deeply inhaled than cigarettes.26 Although the association of smoking marijuana and lung cancer is still unclear, marijuana smoke is associated with inflammation of large airways and increased symptoms of chronic bronchitis.27 Another dangerous possibility is some unregulated marijuana can be laced with other substances such as cocaine, crack, phencyclidine, or formaldehyde.28

Long-term marijuana use can lead to dependence and addiction. Those who begin using marijuana as adolescents are 2 to 4 times more likely to become dependent after 2 years of their first use.29 According to the DSM-IV, 9% of those who try marijuana will become addicted. That number rises to about 1 in 6 among those who start using marijuana as teenagers, and to 25% to 50% among those who use marijuana daily. Cannabis withdrawal symptoms include irritability, sleeping difficulties, dysphoria, craving, and anxiety, which make cessation difficult.17

Strategies for Intervention

Currently, primary care screening tools specific for marijuana use do not exist. Given the adverse outcomes with marijuana use at a young age, it is critical for PCPs to capture high-risk patients early and perform brief in-office interventions. The current gap in literature relating to marijuana-use screening and cessation counseling in the primary care office is no longer acceptable. Equally so, is leaving interventions related to marijuana solely up to mental health providers or substance abuse treatment programs. To examine these gaps and devise strategies for intervention, a pilot study was conducted at an urban clinic in New York City where teens age 14 to 24 years were at especially high risk for drug use and sexual activity.

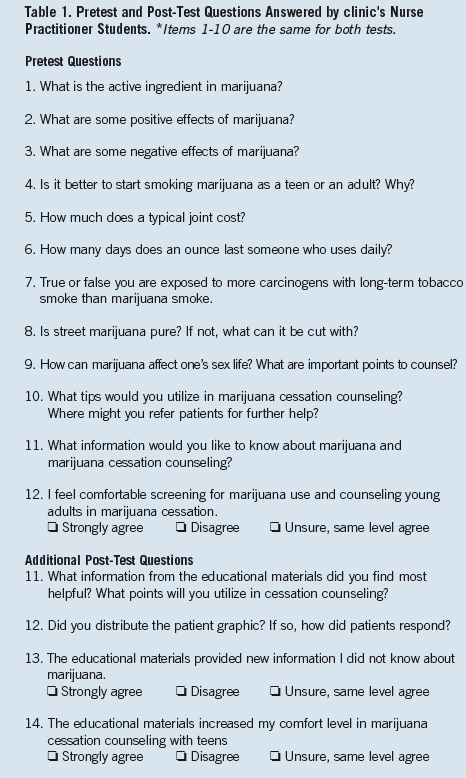

A convenience sample of 8 providers participated in a pretest assessment that evaluated their current knowledge base of marijuana (Table 1) Concurrently, a patient education graphic was developed to facilitate cessation counseling, the ultimate goal of the pilot study.

Over the following 3 months, providers were encouraged to screen for marijuana use utilizing an adaptation of the CAGE questionnaire, commonly used in alcoholism assessment (Table 2), and to conduct brief interventions in the primary care office. After 3 months of intervention, provider knowledge and comfort in screening and cessation were re-evaluated with a post-test. Results showed the percent of providers that answered knowledge-based questions correctly increased for each item from pretest to post-test. Six out of 8 providers agreed they gained new knowledge from the educational materials and overall, there was an 86% increase in comfort with screening and cessation. Patients were not surveyed due to the pilot nature of the trial.

Methods

The pilot study involved 8 nurse practitioner (NP) students at an urban primary care clinic that provides comprehensive care to high-risk and HIV positive youth age 12 to 24 years.

Ultimately, the goal was to:

• Assess providers’ current knowledge base about marijuana and comfort in screening patients

• Educate providers in any knowledge gaps, marijuana cessation, and counseling

• Implement marijuana screening and cessation counseling during primary care visits

• Re-assess providers’ knowledge base, comfort in marijuana cessation screening, and counseling after educational intervention

From the pretest answers, provider educational materials were developed to address knowledge gaps, marijuana use screening tips, cessation counseling strategies, and community resources for further referral. The information and statistics about marijuana were collected from research studies and government reports. The marijuana use screening tool was adapted from the CAGE questionnaire and Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMAHSA) recommendations. Counseling tips were adapted from tobacco cessation recommendations and marijuana specific recommendations by SAMAHSA30 (Table 2).

After developing provider education, a patient education graphic was developed called Marijuana Myth and Fact. Six common myths were selected based on discussions with other providers and the topics were tailored tailoring the topics to those most relevant to adolescents. The patient graphic was edited in collaboration with a physician and a certified family NP, and analyzed via Microsoft Word to be at a sixth grade reading level. Eight nurse NP students were asked to read the provider education materials and discuss marijuana cessation with patients who used marijuana daily. They were encouraged to distribute the marijuana myth and fact graphic to patients as a tool in cessation counseling.

Efficacy of the educational materials was evaluated by a post-test (Table 1), which included the same knowledge questions as those in the pretest, along with 2 additional questions—one about patient response to the graphic, and another about further recommendations for the educational materials. In both the pre- and post-test, 1 point was given for each correctly answered knowledge-based question and “correct” percentages among the 8 NPs were averaged. Scores were compared between the pre- and post-test for each item by calculating the percent increase in number of correct answers.

Results

The findings showed that 100% of the participants correctly answered items on the pretest related to marijuana’s active ingredient, its adverse effects, and how it can impede sex. Although providers scored 100% on many of the pretest questions related to effects of marijuana, the language used was very vague compared to the more concrete physiological effects verbalized in the post-test.

In the post-test, 3 out of 8 providers added medical marijuana-related advantages such as “stimulates appetite” or “decreases ocular pressure.” The percent correct also increased to 100% (Table 3). Language was more concrete, particularly in regard to marijuana’s effects on sex. Though no providers mentioned decreased sperm count and possible decreased fertility in the pretest, at the post-test, 6 out of 8 providers included sperm count in their answers. Furthermore, 87.5% or providers correctly answered marijuana initiation in adolescence is worse than use in adulthood. In the post-test, 100% of providers answered this correctly.

The most missed question with 0% correct on the pretest was how many times a daily user could consume half an ounce of marijuana. Five out of 8 answered correctly on the post-test. Only half of providers knew that marijuana smoke can be more damaging than tobacco smoke in the pretest, 100% correctly answered in the post-test. Although 6 out of 8 providers from the pretest knew that marijuana can be laced with other materials, only 1 out of 8 could identify substances with which it might be laced. At the post-test, 100% of providers could name 1 substance with which street marijuana can be cut. Overall, there was an 86% increase in provider’s comfort with screening for marijuana use and cessation counseling compared to the pretest.

Other Findings

The 3 most commonly requested topics providers wanted more information about were: community resources for patient, how to counsel patients on cessation, and the implications of medical marijuana.

At the pretest, the providers’ aggregate mean disagreed with the statement, “I feel comfortable screening for marijuana use and counseling young adults in marijuana cessation.” In the post-test, the aggregate mean increased to agreeing with the statement. Six out of 8 providers agreed or strongly agreed with earning new information from educational materials (1 provider felt neutral, and 1 strongly disagreed).

One of the most common responses to how patients reacted to the patient education graphic was “surprised.” Providers reported patients were most shocked that smoking marijuana leaves more tar in lungs than cigarettes.26 Patients also were unaware of decreased sperm count, contaminants in marijuana, and brain development impairment. Providers reported some patients agreed with its addictive potential, and saw many of the signs of dependence in themselves. However, some questioned the myths and facts, disagreed with the points, and denied that their daily marijuana use was a problem. Some felt they could quit whenever they wanted to, and just did not want to stop at the time of the visit.

Discussion

This pretest/post-test study found that although PCPs have a general knowledge base about marijuana and its adverse effects, many lack knowledge of its specific physiological and chemical effects (in the brain, lungs, reproductive system) related to early onset of use. Although most providers knew that THC is marijuana’s active ingredient, the majority did not know how it interacts with receptors in the brain impeding brain growth, memory, and coordination. Provider knowledge of marijuana’s benefits was also very general. Although many believed marijuana can aid in relaxation, pain management, and sleep, most were unsure of its exact role in pharmacological therapy (eg, decrease intraocular pressure, relief of nausea, appetite stimulant for AIDS-associated anorexia, and wasting syndrome).13

The purpose of educating providers on the health effects first were so they feel more comfortable educating patients, and have more knowledge to support their cessation counseling. Compared to other illicit substances such as cocaine and heroin, it seems providers are less informed about the adverse effects of marijuana. The provider educational materials were effective in increasing provider knowledge about marijuana. There was an increase in percent answered correctly for each item in the post-test compared to the pretest with the exception of 3 items that scored 100% in the pre-test. Six out of 8 providers also agreed that the educational materials included new information they did not know. The provider feedback that many young clients were surprised with the points on the Marijuana Myth and Fact graphic suggests that providers should regularly educate clients about marijuana use.

The educational materials were also effective in educating providers about how young people are talking about marijuana including street terms and quantitating use. None of the providers correctly estimated how many days 0.5 ounces of marijuana could last (2 weeks) at the pretest, 5 out of 8 answered correctly at the post-test. Understanding street dialogue/slang is important in effective communication and dialogue with young people.

There is currently no widely used tool in the primary care setting to screen for marijuana use, so the majority of providers felt uncomfortable screening for marijuana use at the pretest. Providers found the adaptation of the CAGE questionnaire used to screen alcoholism easy to implement and appreciated the marijuana-specific adaptations. In addition to CAGE, it was important providers asked why teens were using marijuana regularly, because marijuana is often a form of self-medication and escape. The young adults at the surveyed clinic were particularly high-risk and vulnerable, so they may need further referrals to work through the causes of use. It was also essential to ask about safe sex practices while under the influence due to the nature of the population. Additionally, providers were educated to ask if clients knew their dealers and where their marijuana comes from, because of the risk it could be laced with more dangerous substances.

Once providers felt comfortable screening and identifying heavy marijuana users, it was important to have resources for the patients. Many were unaware of where to refer patients for outpatient counseling at the pretest. Six out of 8 providers suggested mental health services, but many clients are resistant to therapy, especially if they are in denial about their marijuana habits. The patient graphic and brief intervention guide gave them new tactics for conducting in-office counseling.

Overall the teen graphic, screening/counseling tools, along with the increased knowledge of marijuana, increased providers’ comfort with marijuana cessation counseling 86% from the pretest. One limitation to this study was the lack of patient feedback. Patients could not personally answer questions related to the patient graphic, its efficacy in reducing use, and further recommendations. Also, the length of the intervention was only 2 months, so some patients who received marijuana cessation counseling initially were not seen again within the time frame. The clinic surveyed was also unique because of its high concentration of medically underserved clients.

The main barrier to successful cessation counseling and positive feedback was patient denial.

Many clients who received the patient graphic expressed to providers they did not have a marijuana use problem. Many believe they can quit anytime, but keep using due to social reasons or just because it is “fun.” It is particularly important to emphasize statistics related to marijuana dependence to these individuals.

Conclusion

Marijuana use is increasing yearly among persons 12 years or older, with about 6600 new users each day.31 With the increasing evidence of adverse health and psychosocial effects of regular marijuana use specifically in adolescent users, early intervention is essential. Using tools like the ones presented in the pilot study, providers can increase their knowledge about marijuana and conduct marijuana cessation counseling in the primary care setting, similar to that of tobacco cessation. Further studies will be needed to investigate if the modified CAGE questionnaire is an effective tool to screen for marijuana use. Additional studies will also be needed to see if educational and counseling materials are effective in modifying behavior.

She Zhao, FNP-BC, is a family practitioner at Lutheran Family Health Centers in Brooklyn, NY. She is a recent graduate of Columbia University School of Nursing with previous experience as a behavioral health case manager and smoking cessation counselor.

References:

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. National survey on drug use and health. Rockville, MD: Substance abuse and Mental Health services administration; 2013.

- Loyola Medicine. Teens who smoke marijuana are at risk of dangerous brain, health disorders. September 25, 2014. http://loyolamedicine.org/newswire/news/teens-who-smoke-marijuana-are-risk-dangerous-brain-health-disorders. Accessed October 2015.

- Nelson S. Obama confused about power to reschedule pot, advocates say. US News. January 31,2014. www.usnews.com/news/articles/2014/01/31/obama-confused-about-power-to-reschedule-pot-advocates-say. Accessed February 2015.

- Lopatto E. Marijuana legalization: what about the teens? Forbes Web site. www.forbes.com/sites/elizabethlopatto/2014/04/24/marijuana-legalization-what-about-the-teens/. Accessed October 2014.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Monitoring the future survey, overview of findings 2014. www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/monitoring-future/monitoring-future-survey-overview-findings-2014. Updated in 2014. Accessed December 2014.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug facts: statistics and trends. www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/marijuana. Accessed in December 2014.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Marijuana. Retrieved from http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/mental/drug-marijuana.shtml. 2013

- Dryden-Edwards R. Marijuana. Medicinenet.com Web site. www.medicinenet.com/marijuana/page4.htm#is_marijuana_addictive. Accessed February 13, 2015.

- Palamar JJ, Ompad DC, Petkova E. Correlates of intentions to use cannabis among US high school seniors in the case of cannabis legalization. Int J Drug Policy. 2014;25(3):424-435.

- Castillo M. Will legalization lead to more teens smoking pot? CBS News Web site. www.cbsnews.com/news/marijuana-legalization-may-lead-more-teens-to-smoke-pot/. Accessed October 2014.

- Silins E, Horwood LJ, Patton GC, et al. Young adult sequelae of adolescent cannabis use: an integrative analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(4):286-293.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Marijuana (Research Reports). www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/marijuana. Published October 2002. Updated December 2014. Accessed December 2014.

- Volkow ND, Baler RD, Compton WM, Weiss SR. Adverse health effects of marijuana use. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(23):2219-2227.

- State marijuana law maps. Governing Web site. www.governing.com/gov-data/safety-justice/state-marijuana-laws-map-medical-recreational.html. Accessed October 2014.

- Halper E. Vermont considers finally just legalizing marijuana. Governing. February 3, 2015. www.governing.com/topics/finance/vt-considers-just-legalizing-pot.html. Accessed October 2014.

- Contorno S. Has the potency of pot changed since President Obama was in high school? Politifact.com Web site. www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/statements/2014/jan/24/patrick-kennedy/has-potency-pot-changed-president-obama-was-high-s/. Published January 24, 2014. Accessed October 2014.

- Hall W. The adverse health effects of cannabis use: what are they, and what are their implications for policy? Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20(6):458-466.

- Swedish. What parents and teens should know about marijuana. http://www.swedish.org/about/blog/december-2013/what-parents-teens-should-know-marijuana. Published December 30, 2013. Accessed October 2014.

- Gogtay N, Giedd JN, Lusk I, et al. Dynamic mapping of human cortical development during childhood through early adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(21):8174-8179.

- Batalla A, Bhattacharrya S, Yucel M, et al. Structural and functional imaging studies in chronic cannabis users: a systematic review of adolescent and adult findings. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e55821.

- Zalesky A, Solowij N, Yucel M, et al. Effect of long-term cannabis use on axonal fibre connectivity. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 7):2245-2455.

- Meier MH, Caspi A, Ambler A, et al. Persistent cannabis users show neuropsychological decline from childhood to midlife. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(40):E2657-2664.

- Fergusson DM, Boden JM. Cannabis use and later life outcomes. Addiction. 2008;103(6):969-976.

- Macleod J, Oakes R, Copello A, et al. Psychological and social sequelae of cannabis and other illicit drug use by young people: a systematic review of longitudinal, general population studies. Lancet. 2004;363(9421):1579-1588.

- Dzodzomenyo S, Stolfi A, Splaingard D, et al. Urine toxicology screen in multiple sleep latency test: the correlation of positive tetrahydrocannabinol, drug negative patients, and narcolepsy. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(2):93-99.

- American Lung Association. Marijuana. www.lung.org/associations/states/colorado/tobacco/marijuana.html. Published in 2014. Accessed December 2014.

- Tashkin DP. Effects of marijuana smoking on the lung. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2013;10(3):239-247.

- University of Maryland Center for Substance Abuse Research. Marijuana. www.cesar.umd.edu/cesar/drugs/marijuana.asp. Published in 2013. Accessed October 2014.

- Chen CY, Storr CL, Anthony JC. Early-onset drug use and risk for drug dependence problems. Addict Behav. 2009;34(3):319-322.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Brief counseling for marijuana dependence. www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/sbirt/brief_counseling_for_marijuana_dependence.pdf. Published in 2005. Accessed October 2013.

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. National survey on drug use and health. Rockville, MD: Substance abuse and Mental Health services administration; 2011.